Blowout on Snorre A – enormous potential for major accident

The Snorre field lies in the Tampen area of the northern North Sea and was one of the original giants on the NCS. Discovered in 1979, it came on stream in 1992 and was producing around 200 000 barrels of oil per day in 2004. Operated originally by Norway’s Saga Petroleum, the field was taken over by Norsk Hydro on 1 January 2000 after Saga had been liquidated. Statoil took it on in turn three years later.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA): Investigation of gas blowout on Snorre A, well 34/7-P31 A 28 November 2004.

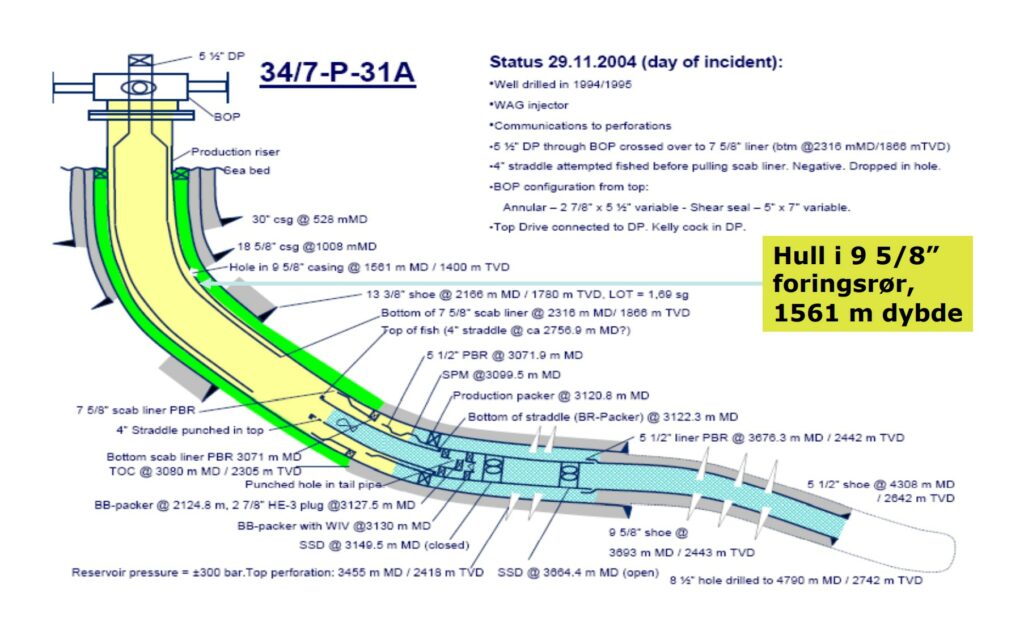

The incident in 2004 occurred in a damaged well. Put simply, wells on a producing field can be used either to produce oil and gas or to inject water/gas. That helps to maintain pressure in the reservoir and thereby recover even more petroleum. The wells in question – 34/7-P-31 and its P-31A sidetrack (a well drilled out from an existing borehole) – were drilled and completed for production in 1994 and 1995 respectively. A number of problems were encountered, including a stuck drillstring and a hole in the casing. That resulted in an unusual completion and a designation as “complex”. After being converted for injection in early 1996, it was found to be damaged in December 2003 and shut down.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA): Investigation of gas blowout on Snorre A, well 34/7-P31 A 28 November 2004.

Drilling wells is time-consuming and expensive, creating an incentive to find ways of making more efficient use of those which already exist. Reusing sections of a well to avoid having to drill some of the length is one approach. The decision was taken in November 2004 to reuse the complex well, with tubing to be pulled out in preparation for drilling P-31B as a new sidetrack. During this work, a not-unknown but unfortunate “piston effect” (called swabbing) occurred. The tubing being withdrawn sucked out what was further down the well – in this case gas.

Alarm sounds and sea boils

The growing problems with P-31A during the afternoon of 28 November were on the agenda at the regular 17.00 meeting of the platform management. A planned emergency response exercise was cancelled, and a crisis meeting called at 19.05. Gas was detected immediately afterwards, although its origin was not tied to the well. It was decided to notify head office, the joint rescue coordination centre (JRCC) at Stavanger Airport Sola, and the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA). A general alarm with mustering at the lifeboats was also activated.

If gas rises in an uncontrolled manner, the falling pressure causes it to expand. Where Snorre is concerned, two cubic metres of gas in the reservoir becomes about 20 cubic metres at the seabed and 200 at atmospheric pressure. Gas from P-31A found its way up the outside of the well tubing and eventually rose to the seabed and the sea surface beneath Snorre A, which is a tension-leg platform (TLP).

At 19.42 that evening, the gas concentration was measured as 60 per cent of the lower explosion limit (LEL), which meant that it was getting close to a level where a single spark could engulf the whole platform in flames.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Leif Sandberg, 20 December 2021, paper, https://www.norskoljeoggass.no/globalassets/dokumenter/drift/presentasjonerarrangementer/kurs-i-arbeidmedisin-2011/3-2-en-utblasning-sett-fra-innsiden-.pdf.

From 21.20 and the following minutes, a number of external gas alarms activated in the same area. Personnel sent to check these out observed that the sea was “boiling” with gas. When this was reported, emergency shutdown was activated manually. Snorre A switched to emergency power and large parts of the platform went dead – not least to eliminate ignition sources. With the flare still burning, the gas could have ignited under slightly different circumstances.

The first stage of helicopter evacuation was implemented from 20.58 to 22.05. Platform manning sank from 216 to 75 people, which included the emergency response team seated in lifeboat 1 and personnel seeking to bring the well under control.

Apart from the danger of gas ignition, the blowout posed a threat that the whole TLP – basically a semi-submersible attached to the seabed by steel tethers – could lose buoyancy and stability. However, continuous monitoring of the tension in each tether showed no change in these during the incident.

Hard choice

One way of fighting a well control incident is “bullheading”, which involves pumping heavy mud at a high rate to prevent the gas flowing up. But initiating emergency shutdown also hit these efforts, because it significantly reduces the power available for such equipment as the drawworks, the rotary table and the mud pumps.

Offshore installation manager (OIM) Dag Lygre and his colleagues in the control room faced a hard choice – restore power to kill the leaking well and risk igniting the gas.

“We’re safe for the next five minutes,” Lygre decided. “And there’s no point in us being here unless we attack the well head on. We must counter it. Kill it. What’s sensible? What can we achieve? What can we think of?”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 6 August 2005.

At 22.45, the decision was taken to restart the main generators. This was regarded as critical but attainable – in part because no gas had been detected on the facility after 21.33. The risky job of restarting the generators was under way just before midnight. But a change in the weather with less wind to blow away the gas prompted the Snorre A crew to prepare once again for a rapid evacuation.

Apart from irregular toilet breaks when they could see the boiling sea for themselves, the emergency response team largely remained in the lifeboat. The team switched boats at one point to get into an area with less gas, and was evacuated by helicopter at 01.25. That left 33 men and two women fighting to control the blowout.

A rising wind and extinguishing the flare combined to reduce the ignition threat. But it was still impossible for supply ships to approach because of gas in the sea, and mud for bullheading had to be mixed on board. Several attempts to pump oil-based mud down the well failed to restore control.

Final attempt

While water has a specific weight of one gram per cubic centimetre (g/cm3), the mud used for bullheading was 1.45 g/cm3. The decision was taken to increase the weight even further for a final attempt using a water-based fluid mixed with barite and bentonite. The crew mixed 160 cubic metres of this substance between 04.00 and 09.52. Its specific weight of 1.8 g/cm3 was better suited to keeping the gas down the well.

Before the mud was pumped down, the pressure in the annulus – the space between the production tubing and the well wall – was measured at 72 bar. It was 156 bar in the tubing. Bullheading began at 09.15. By 10.22, the mud tanks were almost empty – but the pressure was zero bar in both annulus and tubing. The crisis was over.

Serious incident

The PSA appointed a investigation team on the same day to identify nonconformities from the regulations and improvement points – and there was plenty to uncover.

In its report, the team had this to say:

The PSA would characterise this incident as one of the most serious on the NCS. That reflects both its potential and the extensive failure of barriers in planning, execution and follow-up of work on well P-13A. Only chance and favourable circumstances prevented a major accident with the threat of a number of fatalities, environmental harm and further loss of material assets …

The incident could have led under slightly different circumstances to (1) the gas igniting and (2) buoyancy and stability problems with the consequent threat of a number of fatalities, environmental harm and further loss of material assets.[REMOVE]Fotnote: PSA, op.cit.

The report also identified serious failures and deficiencies at every stage in Statoil’s planning and execution related to:

- failure to comply with governing documents

- lack of understanding and conduct of risk assessments

- inadequate management involvement

- breaches of the requirements for well barriers.

The nonconformities reflected failures by individuals and groups in Statoil and at the drilling contractor. These occurred at several levels in the organisation, both onshore and on the facility. No less than 28 nonconformities were identified – 21 on land during the planning phase and seven on the platform. The earliest of these dated back more than a year before the incident.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Leif Sandberg, op.cit.

At the same time, the report praised the commitment shown by those who remained on the facility and noted that this was crucial in preventing the accident becoming even bigger. The platform leadership also won acclaim in other quarters, including from instrument technician and lifeboat coxswain Kirsti Lavold. She was part of the remaining response team, and spent six hours belted up in a lifeboat:

“Then we hear from land that Lygre is being criticised for not evacuating everyone at once. Yes, he could have done that, but then we’d have had another Piper Alpha – although without loss of life, it’s worth noting. But it could have stood and blown for months until a new Red Adair [the American who fought the Ekofisk Bravo blowout in 1976] turned up. That would have been extremely negative for the environment, and attracted massively negative attention to Statoil and Norway. In many ways, he saved Statoil.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 6 August 2005

Anders Lothe, chief safety delegate on Snorre A, maintained that the incident reflected long-standing weaknesses in workplace culture:

“Snorre A has been driven very hard. Like a supercharged car, with the accelerator right down and insufficient maintenance. And Statoil isn’t the only one to blame for this, but also previous owners Saga and Hydro.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 6 August 2005

Snorre resumed oil and gas production in March 2005, 74 days after the drama. The licensees had then “lost” NOK 4 billion in revenues – although the petroleum was still in the ground and could be sold in the future.

The public prosecutor for Rogaland county (which embraces Stavanger) fined Statoil NOK 80 million in 2005, partly on the grounds that “… under slightly different circumstances, a threat would have been posed of a number of fatalities, environmental harm and further loss of material assets. The breaches are regarded as having occurred in particularly aggravating circumstances.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 24 November 2005.

This penalty ranked at the time as the biggest company fine in Norwegian history, and four times larger than Statoil’s previous “record” in the wake of the corruption scandal in Iran.

But how much did it sting? A big fine on the company was not enough, maintained Terje Nustad, president of the Federation of Offshore Workers Trade Unions (OFS): “If it’s going to have any effect, it must be on a par with Statoil’s whole annual profit,” he argued.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 6 August 2005.

According to Oslo business daily Dagens Næringsliv, the fine actually corresponded to one day’s profit net of tax for the company. After giving the matter some thought, Statoil opted to accept the penalty.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 25 November 2005.

arrow_backHelge Lund – commitment to growthGas on hold in Tanzaniaarrow_forward