Winning agreement on a state oil company

The path to deciding how the state should engage with the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) passed through three stages. A first step was taken when the coalition government headed by Per Borten of the Centre Party ensured that the state acquired a majority of the shares in Norsk Hydro.

Even with the state as its majority shareholder, this big chemicals and metals group would be keen as an oil company to preserve its business and freedom of action. Many politicians were therefore unsure whether this was enough to safeguard the state’s interests on the NCS.

Stage two was the 1971 recommendation from the Knudsen commission appointed by the non-socialist government that a wholly state-owned oil company should be established in addition to Hydro in order to take care of the state’s offshore interests. This enterprise would not conduct exploration, production and processing itself, but act as the parent for subsidiaries pursuing active operations.

The third and decisive phase came after the Labour Party’s Trygve Bratteli became prime minister at the head of a minority government in 1971. It wanted to revisit the issue, and a new White Paper on establishing a Norwegian petroleum directorate and a state oil company was presented on 17 March 1972.

This built to a great extent on the principles expressed in the Knudsen commission’s report from the year before, but with one important exception – the state oil company was to be operational. The common foundation provided by the two studies helped to secure broad support in the Storting (parliament).

Tripartite Norwegian model

The Labour Party positioned political heavyweights with solid knowledge of the oil business in the Storting’s standing committee on industry when Bratteli became prime minister. Ingvild Ulveseth was the acting chair, with Rolf Hellem as rapporteur and Harald Løbak as secretary.

This trio helped to retain the important principle of a tripartite Norwegian model, as proposed by the Knudsen commission. Clear boundaries were thereby established between political, administrative and commercial functions.

– Political responsibility for petroleum-related issues was allocated to a dedicated department in the Ministry of Industry, which was to be responsible for legislation and licensing. (This department became a separate Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in 1978.)

– A petroleum directorate would handle the state’s administrative duties by acquiring and processing geological and geophysical data from the NCS. It would also be responsible for seeing to it that the oil industry complied with legislation and statutory regulations, and for that safety and the working environment offshore were looked after.

– A wholly owned state oil company would be established to deal with “the state’s commercial interests and to maintain a collaboration with domestic and foreign oil interests”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 316 to the Storting, see Proposition no 113 (1971-72) to the Storting on establishment of the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate and a state oil company, etc.

Great political agreement prevailed over the these principles.

The company’s object

The Labour Party nevertheless set its clear stamp on oil policy in the new proposition. Compared with the Knudsen commission’s report, the big difference was that nothing more was said about a non-operative holding company. On the contrary, this would be fully operational enterprise.

What activities a new state oil company would pursue was specified for the first time:

The corporate object of Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s is, either by itself or through participation in or together with other companies, to carry out exploration for and production, transport, processing and marketing of petroleum and petroleum-derived products.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

This was further amplified. It was presumed that the company would eventually build up expertise to conduct a range of activities:

– assess blocks where the state had secured the right to participate

– look after the state’s interests in carried-interest agreements

– ensure the practical implementation of the geological and geophysical surveys conducted on behalf of the petroleum directorate

– investigate opportunities in the blocks allocated to the state oil company by the government with a view to identifying the most appropriate disposition of these, including negotiating collaboration agreements on or contracts for utilising the blocks

– participate in drilling operations and production

– participate in transport, refining, marketing and the petrochemical industry to the extent that, and for as long as, this is expedient

– monitor global trends in the petroleum industry, partly in order to assess whether involvement in petroleum sectors in countries other than Norway would be expedient.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

These were extensive assignments for a company which was to be set up and start work from scratch.

Governance of the company

The recommendation to the Storting proposed an active operational oil company with full commercial freedom of action, so that it could take quick decisions if necessary.

Created as a joint-stock company, it would be provided with an initial share capital of NOK 5 million in order to have freedom of action in its start-up phase.

How the company was to be organised was left to its board of directors in collaboration with the Ministry of Industry. The general meeting – in other words, the industry minister – was responsible for electing the directors. In turn, the board was responsible for appointing the company’s chief executive. Key staff would thereafter need to be recruited, and might total 30-40 individuals in the initial period.

Parliamentary management and control was to be ensured through the Storting’s consideration of the company’s operations in connection with the government’s long-term programme, the central government budget and the national planning budget.

The Storting was to be kept informed through the publication of White Papers on the company by the industry ministry at suitable intervals. It was also natural that the company would present long-term plans for its operations. Individual issues of great significance in financial terms or matters of principle had to be submitted separately to the Storting. The latter would draw up regulations on how much of the company’s profit should fall to the government.

The Storting’s industry committee regarded the state oil company as very important for securing national management and control with a view to ensuring that the natural resources on the NCS could be exploited in a way which benefited society as a whole.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Fundamentally, the Conservative Party’s representatives on the committee were undoubtedly always sceptical about establishing a state oil company. At one point, Kåre Willoch, their parliamentary leader, asked them to register dissent. However, they adopted a more pragmatic attitude in order to reach agreement within the committee and concentrated instead on seeking to secure support for limiting the company’s scope for independent action.

Location dominated debate

Establishing a Norwegian Petroleum Directorate and a state oil company was considered by the Storting on 13 June 1972, with Hellem as rapporteur. In his opening speech, he noted that the industry committee’s recommendation – which was unanimously in favour of the proposed state organisation – largely built on the Knudsen commission’s report.

The committee was divided on only one point – not into a majority and minority, but exactly into three camps. This issue involved the siting of the directorate and the company, which were intended to be located in same place.

One faction supported Bergen, another Stavanger – as recommended by the ministry – and third Trondheim. Discussion on this subject was the reason why the Storting took two days rather than one to complete its deliberations.

Hellem proposed Trondheim as the only place in Norway where a technical university could provide the strong scientific capability which could be useful for the state institutions. Moreover, oil exploration would soon move northwards.

Per Hysing-Dahl, a Conservative from Bergen, wanted both directorate and company sited there because the city was already home to a university and the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research.

Labour’s Torbjørn Berntsen advocated Stavanger because this was where the oil industry had already got under way, where the makings of an oil-related community had emerged, and where courses relevant to petroleum operations were being offered by the university college:

Don’t let the state oil company start its work under the serious handicap of being located in places which lie a reassuring distance from the areas where oil activities are under way and will be pursued for many years to come.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting debates (bound edn) 1971-72, vol 116 no 7c, Proceedings of the Storting, no 456.

Industry minister Finn Lied, who had toyed with the idea of Oslo as an option, eventually backed Berntsen’s proposal.

Unanimous decision

While the location debate may have given free rein to the emotions, great agreement prevailed over the recommendation and it was approved unanimously by the Storting on 14 June 1972. The way was thereby finally clear to establish both directorate and company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid, no 460.

The fact that all parties were agreed on establishing the new state oil company was a good starting point. But it was not long before the oil-policy divisions between the non-socialist and socialist parties re-emerged.

Where location was concerned, Stavanger secured 75 votes, Trondheim 49 and Bergen 20.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid. The successful candidate was jubilant at securing both directorate and company for what was already Norway’s oil town.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gunnar Roalkvam og Kristin Øye Gjerde, Oljebyen 1965-2010, bind 4 i Stavanger bys historie, 2012: 77–85.

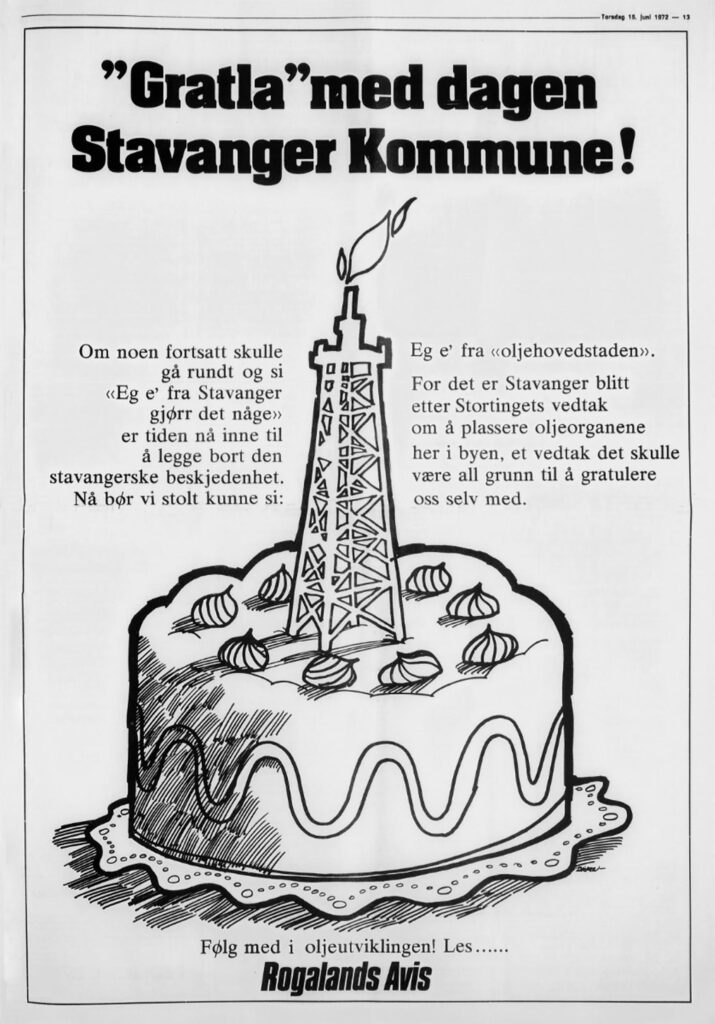

How much various communities around the country felt affected by this issue is reflected in local newspaper headlines the day after the vote.

Stavanger daily Rogalands Avis ran a banner exclaiming “Flags flying in Stavanger”, followed by “Stavanger becomes oil centre” and a comment from mayor Arne Rettedal: “I had my doubts, but they fled quickly. This means a lot for the city’s development.” Rival daily Stavanger Aftenblad also provided broad coverage.

Elsewhere, the story was hardly mentioned. Bergens Tidende had a small item on page 2, while Adresseavisen in Trondheim and Oslo’s Dagbladet wrote nothing at all.

arrow_backThe 10 oil commandmentsControl of Statfjord and the key blocksarrow_forward