Unrewarding power-from-gas efforts

Electricity demand in Norway was rising in the late 1990s. While hydropower continued to meet most of the country’s requirements, a recognition was growing among politicians that this was a limited resource and its large-scale development was over. To spare mountain environments from further extensive water-regulation schemes, the hunt was on for other options.

In addition to developing additional renewable sources, an opportunity existed to fuel power stations from the rich gas resources on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 29 to the Storting (1998-99) – regjeringen.no One argument in favour of such proposals was that Norwegian electricity prices would rise as a result of growing consumption and stagnating hydropower capacity. That would make gas-fired power generation also profitable in Norway.

But what might offer a solution to one problem posed difficulties with another – growing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from ever more extensive petroleum operations on the NCS. Building gas-fired power stations on land would increase Norwegian CO2 emissions and reduce opportunities for Norway to meet its commitments under the Kyoto protocol on keeping such releases at the 1990 level.

Rivals unite

Since the 1980s, Statoil, Norsk Hydro and hydro-electricity generator Statkraft had competed over developing rival gas-fired power projects. That gave way in the 1990s to a collaboration between the three. Established in 1994, Naturkraft A/S was initially owned 50-50 by Statoil and Statkraft, while Hydro became involved later. Its business concept was to sell gas-fired electricity to Finland and Denmark as a replacement for coal-fired power. That would help to reduce GHG emissions from these countries.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas, 2015, Da gassen kom til Norge: 284.

At its meeting of 22 February 1996, the Statoil board approved participation in two planned gas-fired power stations to be built and operated by Naturkraft. One would be at Kårstø north of the Stavanger, based on gas from Statfjord and other fields, and the other at Kollsnes near Bergen. This would take its fuel from the Troll field, which had recently come on stream. Statoil agreed to contribute NOK 670 million and NOK 700 million respectively to these projects.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board meeting, Statoil, item 1/96-6: Naturkraft: bygging av gasskraftverk.

The Storting (parliament) approved construction of the two facilities in June 1996. Naturkraft received a licence in the same year and emission permits in 1997 for both Kårstø and Kollsnes. These decisions were controversial. An alliance of environmental organisations collected 100 000 signatures opposing the construction plans. Even bishops protested, while marches and campaigns were staged – particularly at Kollsnes, where demonstrators established a summer camp for several weeks in 1997.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas, op.cit: 284.

Hydro goes it alone

Without the knowledge of the Naturkraft leadership, Hydro now came up with a new proposal. It wanted to build a gas-fired power station on Karmøy island, which is crossed by the gas pipeline on its way to Kårstø. This facility would burn hydrogen produced from methane.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ekspertintervjuet: Slik lages hydrogen fra naturgass | Blått hydrogen lages av naturgass med karbonfangst. Professor Hilde Johnsen Venvik forklarer hvordan det gjøres, og hvorfor hun tror vi trenger også det dersom vi skal lykkes med Det grønne skiftet. (energiogklima.no). CO2 from hydrogen production could be piped offshore to the Grane field for subsurface deposition. That would allow Hydro both to generate more power for its own industrial plants on land and provided valuable pressure support for oil production in the North Sea. Achieving all this without CO2 emissions seemed an excellent idea.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas, op.cit: 285.

Hydro’s ideas were greeted with acclaim by politicians and environmental campaigners. To the company’s disappointment, however, it soon transpired that an emission-free gas-fired power station on Karmøy lacked viability because the technology was expensive and still had to be matured. Grane was developed without CO2 from land.

Storting debate and government crisis

The controversies continued in the Storting’s corridors. A recommendation on developing gas-fired power stations and the requirements which should be set for GHG emissions came up for consideration in the spring of 2000.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sak – stortinget.no Recommendation no 122 to the Storting (1999-2000) – stortinget.no. The centre-right coalition led by Christian Democrat Kjell Magne Bondevik wanted to set tougher emission requirements in Norway than in other members of the European Economic Area (EEA), but this was voted down by a Storting majority of 81 to 71 votes. A proposal from Labour and the Conservatives to amend the Pollution Control Act in order to open the way for gas-fired power stations was approved by 104 to 48 votes.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nrk.no/urix/bondevik-stiller-kabinettsporsmal-1.462317. Since Bondevik had made this an issue of confidence, the government resigned on 10 March – probably the first time that has happened over a climate issue.

In political terms, the way was then clear for Naturkraft to start construction. As a compromise, the licences for the power stations were modified to impose a requirement to develop plans for future carbon capture and storage (CCS) solutions. Combined with a government order to purchase CO2 emission allowances, however, this demand weakened the economics of the projects.

Gas-fired power station at Kårstø

Statoil CEO Olav Fjell required a return of 12 per cent after tax for all larger projects. This was regarded as unrealistic at Kårstø, and Statoil opted in 2004 to sell out of Naturkraft. Instead, it considered building gas-fired power stations at Tjeldbergodden in mid-Norway and Mongstad near Bergen.

Hydro and Statkraft continued with the Kårstø plans. Just before the opening of Norway’s first large gas-fired power station, however, Statoil was back as a shareholder in Naturkraft following its merger with Hydro’s oil and energy division.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas, op.cit 286.

The Kårstø facility stood in the same area as the natural gas process plant. Delivered by Siemens, it was fuelled by gas from the North Sea and had an installed output of 420 MW. Under optimum conditions, it could generate about 3.5 TWh per annum – enough to supply electricity to 219 000 Norwegian households, or twice Stavanger’s population at that time.[REMOVE]Fotnote: These figures are based on the calculation by Statistics Norway that average annual Norwegian electricity consumption per household is 16 000 kWh. Normalt strømforbruk | Gjennomsnittlig etter kvm (i 2022) (forbrukerguiden.no). The population of Stavanger in 2007 was 117 000. That would consume 600 million standard cubic metres of gas per annum, roughly 0.5 per cent of Norwegian gas production.

According to the experts, the power station had an efficiency of 58-59 per cent. This was considered very high. The downside was that it released large quantities of CO2 – about 1.2 million tonnes a year in full operation.

These emissions carried a cost. The facility initially received free emission allowances. Once these were used up, however, it had to buy additional allowances which further weakened its profitability. Low power prices and poor profitability meant that the power station remained idle for long periods. When electricity prices were so low that they failed to cover even ongoing operating costs, shutting down cost less than maintaining output.

Plans to establish a facility for CO2 management were eventually shelved, but preparations were nevertheless made for installing capture equipment at a later time.

High gas prices and low electricity charges made it difficult to operate profitably after 2011. The Naturkraft board therefore decided in October 2014 to mothball the power station. Operation ceased and the organisation was disbanded without removing the actual plant and associated equipment. In 2017, however, the power station was nevertheless dismantled and the gas turbine sold back to Siemens.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://snl.no/K%C3%A5rst%C3%B8_kraftverk.

Gas-fired power station at Mongstad

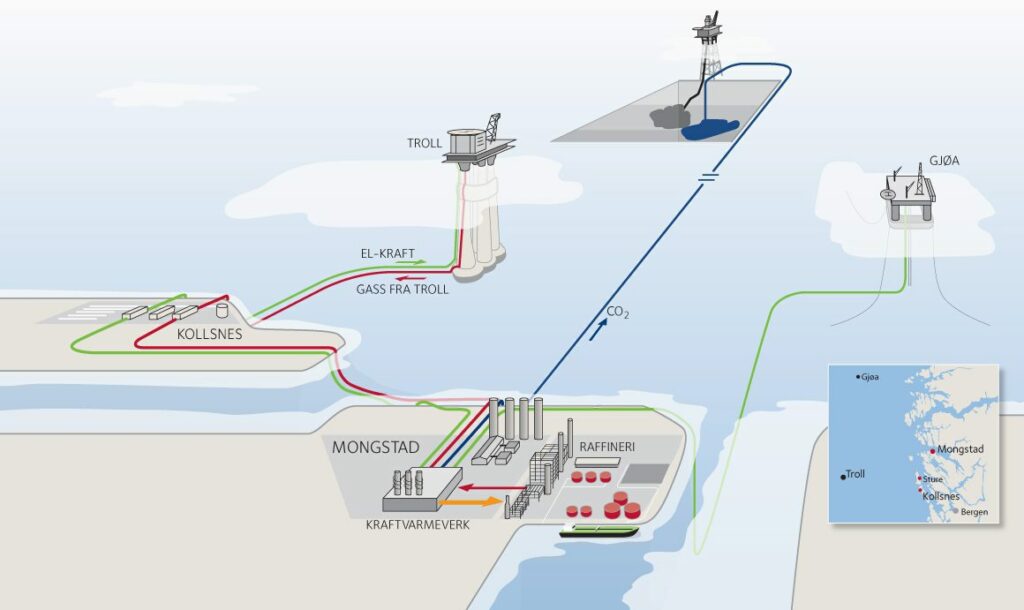

The previously planned gas-fired power station at Kollsnes was never built. Instead, an opportunity opened at Mongstad. A lot of heat went to waste at the ageing refinery there, which was owned at that time 79 per cent by Statoil and 21 per cent by Shell. Plans were drawn up for a new gas-fuelled combined heat and power (CHP) station which would be integrated with the refinery and could substantially improve efficiency.

Gas from the Troll field could be used as fuel for the facility because a new pipeline for natural gas liquids from the Kollsnes terminal to the refinery was ready in 2004. Natural gas arriving from Troll and Kvitebjørn could then be sent on to Mongstad for fractionation or as fuel for CHP.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2004, Statoil. On 12 October 2006, Statoil received permission to build this Mongstad energy plant (EVM). Construction work on the facility, which would both produce steam or hot water at 120-140°C and generate electricity, began in January 2007.[REMOVE]Fotnote: kraftvarmeverk – Store norske leksikon (snl.no).

An agreement was moreover reached in 2006 by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) and Statoil on developing solutions for future carbon capture. A technology company was to be established to pursue the first construction phase of a plant capable of handling 100 000 tonnes of CO2 per annum. The goal was to test, qualify and develop solutions for carbon capture which could reduce costs and risk. If this succeeded, it might be possible to build a full-scale capture facility at the refinery.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2006, Statoil: 3. This ranked as a prestige project for the Labour government led by Jens Stoltenberg, which was intended to show the world that full-scale CCS could be achieved. It was perceived as being equivalent to the US Moon landing drive in the 1960s. Any new technology would help not only Norway but also other countries to reduce their GHG emissions.

Statoil had several reasons for wanting to collaborate with the government in this way. First, the licensing terms imposed for the power station in 2006 required CCS. Second, helping to identify new solutions for reducing GHG emissions would give the company an opportunity to improve its environmental reputation without excessive cost since the government was to foot much of the development bill. Statoil was already known as an early and bold technology adopter, and this could help confirm that image.

Following a trial period in 2009, the CHP facility began commercial operation on 20 December 2010. The gas and steam turbines for generating electricity and heat respectively were delivered by General Electric. A total capacity of 630 MW was divided between 280 MW in electricity output and 350 MW/second in the form of heat delivered to the refinery. The station could thereby deliver about 2.3 TWh of power annually, compared with 3.5 TWh for the Kårstø facility.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energiverk_Mongstad.

The Mongstad plant was initially built and operated by Dong Energy, but was taken over wholly by Statoil in 2013.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://orsted.com/en/company-announcement-list/2013/07/1192981. Total construction costs were estimated at NOK 4 billion.

Even after the EVM became operational, it only generated electricity for about half the available hours.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 26 August 2012 https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/P9RVR/jeg-liker-ikke-aa-si-at-jeg-hadde-rett-men-fakta-taler-for-seg-selv. It was hit, like the Kårstø facility, by high gas and low power prices. The trial project to build a carbon capture plant for the CHP station and inject CO2 into a formation beneath the North Sea was shelved by the MPE in 2013 because it was too expensive and the technology insufficiently mature. Follow-up of the project by the government came in for criticism from the Storting.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Saker/Sak/?p=58007.

After losses in the order of a hundred million kroner over several years, Statoil decided to shut down the controversial gas-fired power station in 2017. It operated with a single gas turbine and the steam turbine from January 2019, and the last gas turbine was due to go off-line in November 2020.

The intention was to begin decommissioning the station on 30 August 2022, but grid operator Statnett asked Equinor in July to continue operating the EVM. That reflected the electricity crisis which hit the country after it began exporting more power to the UK in the autumn of 2021, and the loss of Russian gas exports to Europe following the outbreak of war with Ukraine in February 2022.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nrk.no/nyheter/statnett-ber-equinor-utsette-nedstengningen-av-gasskraftverket-pa-mongstad-1.16055405.

Although Statnett considered the possibility of electricity rationing in Norway from the winter of 2022 to be “up to 20 per cent”, CEO Anders Opedal responded that, as a normal listed company, the supply position was not Equinor’s problem.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), “Statnett ber Equinor utsetje nedstenginga av gasskraftverket på Mongstad,” 2 August 2022. This again highlighted the dilemma faced by the company with the state as its majority shareholder, as did the “Moon landing” project. Equinor remains under pressure to serve as a political instrument for the government, whether management and the other shareholders like it or not.

arrow_backLong wooing for access to RussiaMusic 303 metres downarrow_forward