Quiet in the ranks on land

Statoil CEO Arve Johnsen, Jens Christian Hauge, its first chair, and his successor Finn Lied all had deep roots in the labour movement. Under their leadership, the company took it for granted that unions would be a party to collective pay talks as well as agreements on working hours and other employment conditions.

This was not a normal standpoint in the international oil companies with subsidiaries in Norway. US companies such as Phillips Petroleum Company and Mobil preferred non-union labour. They could at a pinch accept “company” or “yellow” organisation – in other words, bodies under their domination and unaffiliated to the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, 1988, Gjennombrudd og vekst: Statoil-år 1978–1987: 171.

In Johnsen’s view, such organisations were objectionable, since they were not concerned to fall in line with the rules governing working life in mainland Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Fossen Lange, Alexander, Den solidariske petroleumskapitalist, Masteroppgave historie (2020) . He therefore gave emphasis to making provision for union work in the company.

Statoil’s first unions

As long as Statoil was not an operator, it has no employees working on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).[REMOVE]Fotnote: The first Statoil employees to work offshore were on Statpipe riser platform 2/4 S on the Ekofisk field from January 1984. Its own personnel worked on land, and it was they who established the company’s first unions.

However, the personnel association created in 1976 to deal with welfare issues for Statoil employees cannot be classified as a union.

The company’s first proper organisation of this kind was the local branch of the Norwegian Oil and Petrochemical Workers Union (Nopef). This was founded in March 1977, soon after Nopef had become a LO member. In June that year, a collective agreement on pay and conditions was negotiated between the union and Statoil. Its branch then had 30 members and was chaired by Jon Bakken. The pay deal was largely based on the main agreements negotiated by the LO with the civil service and the Norwegian Employers Confederation (NAF). Pay terms in the company were discussed, and both sides agreed to collaborate further on these.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 10/77, “Avtale mellom Statoil og NOPEF undertegnet”.

Branches were then established in quick succession by the Norwegian Society of Chartered Engineers (NIF), the Norwegian Society of Engineers (Nito) and the the Norwegian Association for Salaried Employees (NAS).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, op.cit. By 1978, about a quarter of the 600 employees were unionised.

The introduction of Norway’s Working Environment Act on 1 July 1977 helped to emphasise that the company was required to have orderly labour relations. Statoil’s management wanted it to lead the way in this area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 10/77, “Ny lov om arbeidervern og arbeidsmiljø”. To meet the Act’s requirements, a working environment committee (AMU) was established in 1977 and merged fairly quickly with the works council set up in 1974.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The works council had dealt with such matters as employment rules, further education, the company health service, safety, flexible working, canteen operation and day care nursery provision.

Not a pacesetter

Although Statoil was wholly state-owned, it was also an industrial enterprise and a limited company similar to the other members of the NAF. A moderate approach was initially taken to remuneration, since Johnsen did not want the company to be a pacesetter on pay.

Policy in this area built on determining rates individually in relation to performance, with the emphasis on professional ability, commitment, efficiency, initiative, ability to collaborate, responsibility and loyalty.

Raises would have a low-pay profile.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 10/77, “Mer om lønnsregulering 1977”. They were awarded on the basis of guidance in remuneration scales developed by Statoil on the basis of statistics from employer associations and unions, and on comparisons with other companies.

Pay negotiations were based almost wholly on the national LO/NAF collective settlement.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nb.no/items/81b2b8a1faa11545b2b7eee300178fc9?page=1&searchText=. Statoil thereby demonstrated clear loyalty to the Norwegian model for labour relations.

The company’s goal in 1977 was an average rise in real pay of 2.5 per cent from the year before. But the workforce achieved a far better outcome, averaging a 10.9 per cent increase. Statoil’s employees were thereby privileged by comparison with those in many other Norwegian firms, but not necessary in relation to personnel at other oil companies in Norway.

Moderation was urged at the board meeting of 29 June 1978, when the country faced an economic crisis. Applied particularly to those on the highest salaries, this presented a challenge given that pay levels in operator companies Mobil, Phillips and Elf were often considerably higher than in Statoil.

Competition over engineers was intense in Norway’s rapidly expanding oil sector. Its lack of operator status meant that Statoil could not offer the most challenging and interesting jobs. Nevertheless, many wanted to work for the new Norwegian oil company.

To reward technical specialists, they were given a framework pay rise of 8.2 per cent in 1977. That compared with five per cent for other highly paid personnel.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board minutes, Statoil, item 7/78-13, “Den generelle lønnsregulering i Statoil per 1.7.1978”. https://media.digitalarkivet.no/view/22486/202.

Things got tighter after the government imposed a ban on pay and price rises for Norwegian industry from 12 September 1978 to the end of 1979. But the lag in pay rates which thereby arose had been closed again as early as 1980. Statfjord was then on stream, and Statoil was starting to make money. The collective pay settlement that year ended up with an average raise of 13.58 per cent. That was within the ceiling imposed by the Statoil board, in line with the parameters agreed by the LO and the NAF, and a straightforward adjustment to rates in the pay system.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nb.no/items/81b2b8a1faa11545b2b7eee300178fc9?page=1&searchText=.

Conflicts were offshore

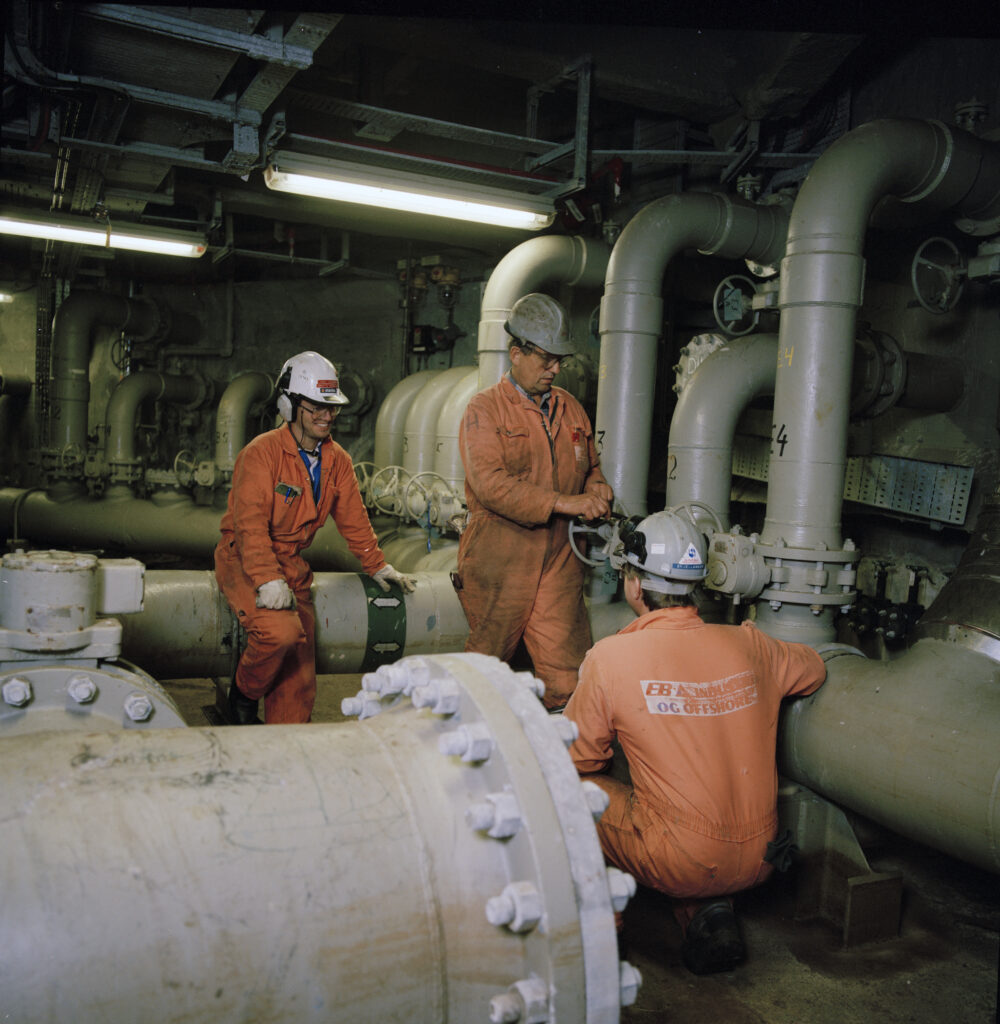

While pay settlements for Statoil personnel on land were agreed without difficulties, relations between employees and employers in the oil and supplier companies become tougher through the 1980s. Many strikes occurred, winning offshore workers increased pay. The government responded to these stoppages with the regular imposition of compulsory arbitration.

When Statoil became the operator of Statfjord in 1987, the existing Statfjord Workers Union (SaF) joined the ranks of the company’s trade unions. Originally a company union on the field, the SaF had become a member of the Collaboration Committee for Operator Unions – later the Federation of Oil Workers’ Trade Unions (OFS). It had a tradition of downing tools to reach its goals. That created more turbulence than had been customary in the Statoil system, and led to the toughest strike in its history.

arrow_backLetter from the NPDDiscovering Gullfaks: Hiccups and Blowoutsarrow_forward