Off Canada’s east coast

Biggest discovery of 2013

After the 2007 merger, the interests previously held in Terra Nova (15 per cent) and Hibernia (five per cent) formed the nucleus of StatoilHydro’s Canadian offshore activity. These two producing fields lay in the Jeanne d’Arc Basin off Newfoundland. As mature producers, they contributed substantial revenues to their licensees and provided a good basis for the big new Norwegian company’s continued involvement.

Several opportunities lay open, including the largest holdings in two discoveries – Hebron and Hibernia Southern Extension. StatoilHydro also had interests in six offshore exploration licences, two production licences and 28 other licences where hydrocarbons had been discovered.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, StatoilHydro.

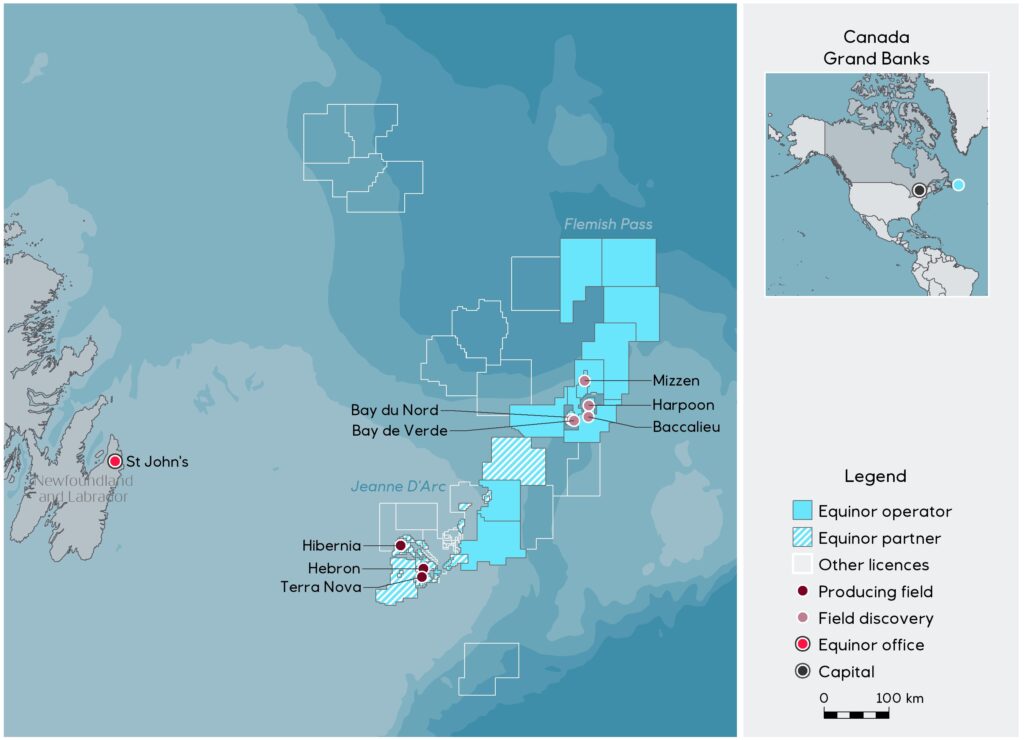

Statoil, as the company was once again called after 2009, aimed to become a production operator. In that respect, 2013 proved memorable. Exploration drilling 500 kilometres east of Newfoundland, in the Bay du Nord area, proved an oil discovery with great potential – and the largest made anywhere in the world that year. Some 300-600 million barrels of recoverable crude were indicated. It was described as light and fine, in a good-quality reservoir.

An earlier discovery with Statoil participation in the Harpoon prospect was estimated to contain 100-200 million recoverable barrels, while a third find – Mizzen – in the Flemish Pass Basin was under evaluation to establish whether this represented a completely new oil basin off Newfoundland.

The very largest discovery was made in around 1 100-1 200 metres of water in the Bay du Nord, and covered a huge 8 500 square kilometres. That the finds were spread across a big geographical area in the Flemish Pass Basin, a long way from land, made finding a good development solution demanding.

But Tim Dodson, executive vice president for exploration at Statoil, nevertheless believed that this discovery brought the company – as exploration operator with a 65 per cent holding in the Bay du Nord – a good step closer to the development operator role. The other 35 per cent was held by Canada’s Husky Energy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 26 September 2013, “Oljefunn med stort potensial for Statoil i Canada”.

Icebergs from Greenland

Several factors complicate developments in Bay du Nord. One is the field’s location 500 kilometres from land, with no existing infrastructure in the form of pipelines. Another is icebergs from Greenland, which drift south past Newfoundland every year. During the summer season, when Greenland’s glaciers calve, roughly 1 000 bergs pass the discovery site over three-four months.

Statoil worked with full vigour in 2014 to secure an overview of how this natural phenomenon could be managed. Data acquired over many years could be used as a basis for predicting ice movements. Satellite monitoring and regular overflights of the area would also be necessary to keep track of the bergs.

If these massive floaters fail to behave as expected, icebreakers and supply ships can try to change their course by towing them away. Should a berg nevertheless enter the operational zone, the installations can in the worst case be disconnected and moved away to avoid the Titanic’s fate.

Before any development decision could be taken, a number of exploration wells were drilled in the area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: E24, 8 May 2014, “Slik skal Statoil takle isfjell i Canada”. The Bay de Verde discovery was proved in 2015 and Baccalieu the year after. In Statoil’s view, a development project in the inhospitable climate and deep water of the Bay du Nord fits well with its experience from the NCS.

Development plans

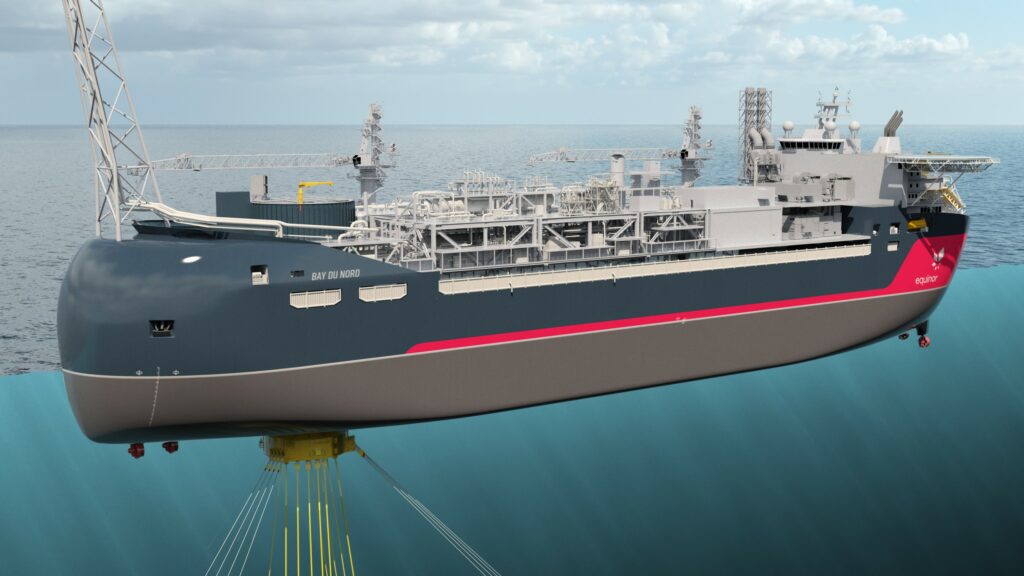

The Canadian government finally gave the green light for the Bay du Nord project in April 2022. A development concept had then been produced which comprises subsea installations tied back to a monohull floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) unit which can store and offload oil to shuttle tankers for shipment to refineries. The field is expected to yield 300 million barrels of oil over 30 years.

This project will benefit Canada economically. Development costs are put at CAD 10.9 billion over the field’s producing life. That will provide jobs and work for local industry. The government of Newfoundland and Labrador could receive CAD 3.5 billion in tax revenues.

As of July 2022, Equinor has not yet decided on development.

Stringent green requirements

Approval of the development took so many years because it was postponed many times after the Canadian government under Justin Trudeau decided, in accordance with the Paris agreement, on a 40-45 per cent cut in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the 2005 level by 2030.

A four-year environmental impact assessment commissioned by Equinor was needed before the go-ahead was given. The government had then set 137 binding conditions, including a reduction in GHG emissions, protection of fishing grounds and air quality safeguards. They represented “some of the strictest environmental requirements ever” in the country, according to Canadian environment minister Steven Guilbeault.

The environmental organisations were nevertheless dissatisfied and pointed to UN warnings that new oil fields should be left undeveloped to avoid irreversible and destructive climate consequences.[REMOVE]Fotnote: DN, 7 April 2022, “Canada gir grønt lys for Equinor-prosjekt”, https://www.dn.no/utenriks/equinor/canada/canada-gir-gront-lys-for-equinor-prosjekt/2-1-1198059.

All the same, Guilbeault defended the commitment. GHG emissions from this type of oil production would be very much lower than from oil sands and five times below the average for Canadian oil projects. The project would be “an example of how Canada can carve out a way forward by producing energy with the lowest possible emissions while we move towards a zero-emission future”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.