Irish gas with sour taste

Ireland was long one of Europe’s poorest nations, with huge emigration to the USA. The Catholic country was effectively a British colony for centuries, until full independence in 1937. After joining the EU in 1973, the Irish government made provision for foreign enterprises to establish themselves in order to boost the economy. Among the inducements on offer were low taxes – attractive for international oil companies when offshore acreage was put on offer.

Finding Corrib

Both Statoil – through its UK subsidiary – and Saga Petroleum applied for licences on the Irish continental shelf in 1993, and both secured interests in the block where Corrib was found. This lay in 350 metres of water almost 90 kilometres off the north-west coast.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nb.no/items/afc5a630cc1271bca69f92b7ba417047?page=23&searchText=, accessed 6 December 2021.

Statoil had faith in its opportunities in Ireland and opened an office in Dublin. It then expanded operations both there and in the UK by acquiring Aran Energy Plc, which included the operatorship for several blocks on the Connemara field off western Ireland. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1995, Statoil. Unfortunately, these deposits proved non-commercial as early as 1997. That resulted in a loss of NOK 1.2 billion for Statoil – not a good start in the country.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1997, Statoil.

But Corrib continued to offer opportunities. When Saga was wound up in 1999, Statoil took over that company’s interest in the field and raised its share to 36.5 per cent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1999, Statoil. Enterprise was operator with 45 per cent and responsible for development planning, while Marathon had an 18.5 per cent stake.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Slevin, Amanda, 2016, Gas, oil and the Irish state: 9.

Plans for developing the gas field, approved by the Irish government in 2001, called for production to begin within a couple of years. Soon afterwards, Shell merged with Enterprise and took over the operatorship.

Corrib was originally due to be developed by drilling seven subsea wells in 350 metres of water with no offshore platform. Gas would be piped to the small village of Rossport in Mayo county. It would then be transmitted to the Bellanaboy Bridge gas terminal about nine kilometres away, while a new tie-in was to be constructed to Ireland’s existing gas network.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2001, Statoil.

Protests and big delays

Local opposition to the overland pipeline route and the terminal emerged as early as the late 1990s, even though the government hailed the project as good news for creating jobs and activity. The locals did not feel they had been taken into account, since they were not consulted and received only indirect information via the press.

They posed several critical questions. They included whether the terminal, located by a narrow estuary, would cause pollution harmful to the fish or whether discharges might affect sources of drinking water further inland. Others focused on how the pipeline would affect the landscape, how high its internal pressure was since it ran close to homes, and whether it could explode. The fact that the developer used Enterprise, a British company, to investigate the environmental impact added to scepticism. Plans to use British rather than domestic workers offshore were perceived as anti-Irish.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Slevin, Amanda, op.cit: 11-15.

In this climate, characterised by fear and suspicion, opposition grew. The division of the project into three parts – offshore, pipeline and terminal – meant many separate decisions were required, which offered rich opportunities for spinning this out the process. Initial protests focused on the terminal, which finally passed all the legal hurdles in 2004.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 24-25. Work offshore and on land then continued with the aim of coming on stream in 2007.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2004, Statoil. To the surprise of the oil companies, the protests gathered strength. Their focus was now on the nine-kilometre pipeline route over land.

In 2002, the Irish government had given Shell a green light to cross private property without the consent of its owner. Most of the 34 parties concerned had accepted the pipeline. However, farmers Micheal O Seighin, Vincent and Phillip McGrath, Willie Corduff and Brendan Philbin opposed access. They were taken to court, where Shell won its case. But the Rossport five refused to budge and were jailed on 29 January 2005. They stayed inside for 94 days, arousing anger both locally and nationally and attracting international notice.

Shell agreed to await an independent review of the project and attempted mediation with the local community. The result was a recommendation to reduce the operating pressure in the pipeline and to seek a new route.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, 2021, 50 år med oljeproduksjon. Min historie, privately published: 269-272.

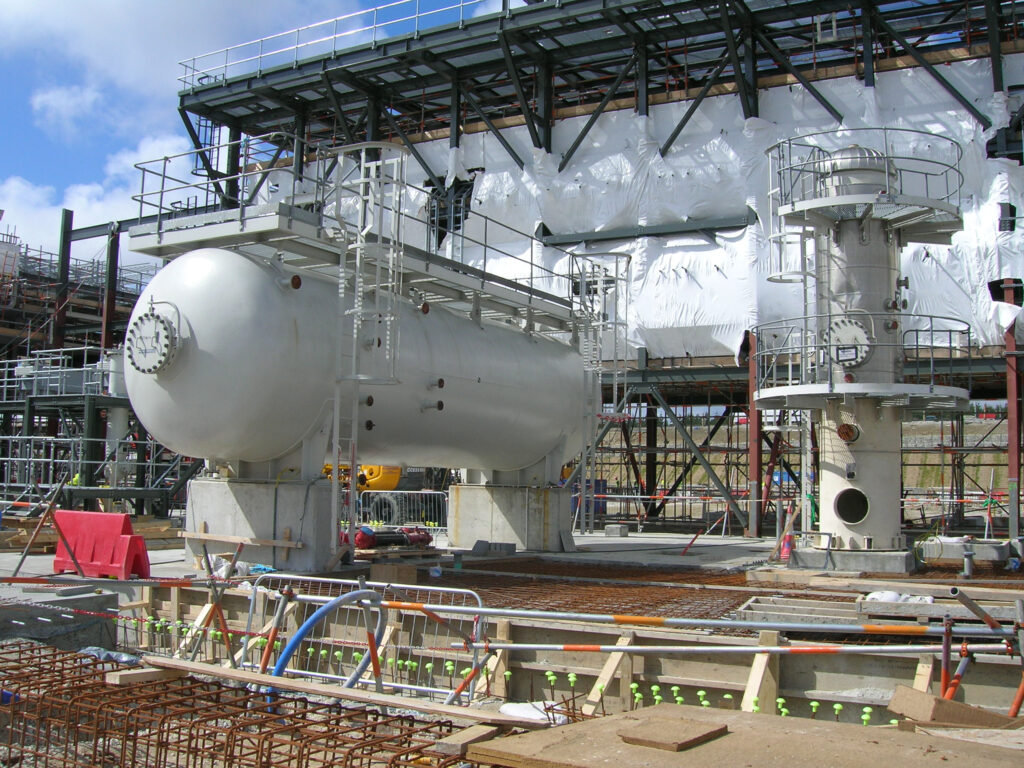

All the wells and the pipeline to land were in place by 2007-08, followed by the terminal in 2009. All that remained was the onshore pipeline. The first route on the north side of the estuary was abandoned. Plans to follow the southern shore were rejected because of a landslide hazard in one area. A third proposal to lay the pipeline up the estuary itself had to be dropped because installation work would stir up mud in the water which could in turn damage two mussel farms. The final solution was to drive a five-kilometre tunnel under the estuary.

Protests spread to large parts of Ireland. Several independent members of parliament supported the campaigners, and young environmentalists poured into the construction area over several summers. Some camped in tents and disrupted pipelaying by paddling kayaks across the course of work vessels. Construction machinery and materials were sabotaged by cutting cables and hydraulic hoses. Shell hired security guards to protect against such damage, and protests were also directed at Statoil. Demonstrators with placards appeared outside the Norwegian embassy in Dublin on several occasions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The most effective opposition came from those who studied Ireland’s unclear regulations and exploited them to make a string of complaints to the authorities. On each occasion, a committee was appointed by the local authorities, the central government or EU agencies to consider the matter. These always concluded that the project could continue, but a new delaying complaint had by then been received.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Losses for everyone

It was not until 2015 that Shell was able to complete the Corrib development – 19 years after the gas had first been discovered. Initially costed at EUR 850 million, the project’s final price tag was EUR 3.8-4 billion.

Corrib has been Statoil’s only development in Ireland. According to the Irish Independent, its overall loss up to 2015 was EUR 243 million – the company’s biggest overrun until then.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Shell completes Corrib as partner confirms €243m loss – Independent.ie, 18 September 2015. Accessed 6 December 2021.

The financial risk of the project was nevertheless reduced because the oil companies could deduct their development costs from production profits. Under the Irish tax regime, this allowance was 100 per cent – compared with 78 per cent in Norway. In Corrib case, the huge extra costs affected Ireland’s tax revenues. Moreover, corporation tax in Ireland was 25 per cent as against Norway’s 78 per cent for oil companies. The Irish government thereby failed to make much from Corrib. For its part, Statoil’s board considered that revenues from the field would be sufficient to make it profitable in the future.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, “Statoil har tapt 7,7 milliarder i Irland”, 22 September 2015.

On reflection

Looking back, many aspects of the Corrib development helped to escalate the conflict between Shell as operator and the local population. Lack of information and dialogue, fears of harm to the natural environment, memories of British oppression, exploitation of the legal system and inadequate legislation were key factors.

Helge Hatlestad, senior vice president for international development and production in Statoil, held several meetings with Irish politicians and conversations with locals in Rossport. He grasped that much of the suspicion arose because a British company was in charge. It would have been better to use Irish personnel at every level. And the locals should have been better informed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, op.cit: 269-272.

Whether another approach would have been enough to allay the opposition is a hypothetical question. A detailed view of the conflict is provided by Gas, oil and the Irish state by Amanda Slevin. She also compares Norwegian and Irish oil policy. The story of the Rossport Five, in particular, has left marks. A documentary entitled The Pipe has subsequently been made and – in good Irish tradition – the story lives on in musical form.

Out of Ireland

Equinor resolved in November 2021 to terminate all involvement in Ireland, after commitments associated with licence options obtained in the Porcupine Basin in 2016 were fulfilled. These had covered acquisition of two- and three-dimensional seismic data in an area where water depths vary between 1 100 and 3 150 metres. Four of the options involved licence operatorships, and two covered participation as a partner with ExxonMobil. But Equinor decided not to proceed to exploration drilling.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Statoil, “Statoil tildelt letelisenser utenfor kysten av Irland”, 2 March 2016. The group had also been assessing opportunities for wind power off Ireland together with Irish partner ESB.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/content/statoil/search.html?language=en&q=Ireland, accessed 6 December 2021. But it decided to pull out while this project was still in an early phase.

Corrib had been Statoil/Equinor’s most important engagement in Ireland, but it was decided to withdraw from this venture as well. Vermilion Energy Inc, the operator with 20 per cent, agreed to buy Equinor’s 36.5 per cent share for USD 434 million with effect from 1 January 2022.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Equinor, “Equinor sells its non-operated position in the Corrib gas project in Ireland”, 29 November 2021. The other partner, Nephin Energy, had 43.5 per cent.

The sale of Corrib meant in effect that Equinor no longer had any active operations in Ireland. That was in line with the group’s strategy under CEO Anders Opedal to concentrate the business. Selling out of the Irish field freed up capital which could be reinvested elsewhere, according to Arne Gürtner, senior vice president for the UK and Ireland at Equinor.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.