How Statoil landed the golden block

Statoil ranked in 1977 as a privileged company. It had been awarded half the Norwegian share of Statfjord outside the regular licensing rounds and was now in full swing – together with operator Mobil – on planning and developing this field. So the company held 50 per cent of the largest oil field discovered on the NCS and was being trained in a large and complex development project by a major oil multinational with much experience. It was thereby ready for new tasks, preferably a major operatorship, and block 34/10 was at the top of its wish list. But, as always where its position, power and strength were concerned, political conflicts arose.

Wish list

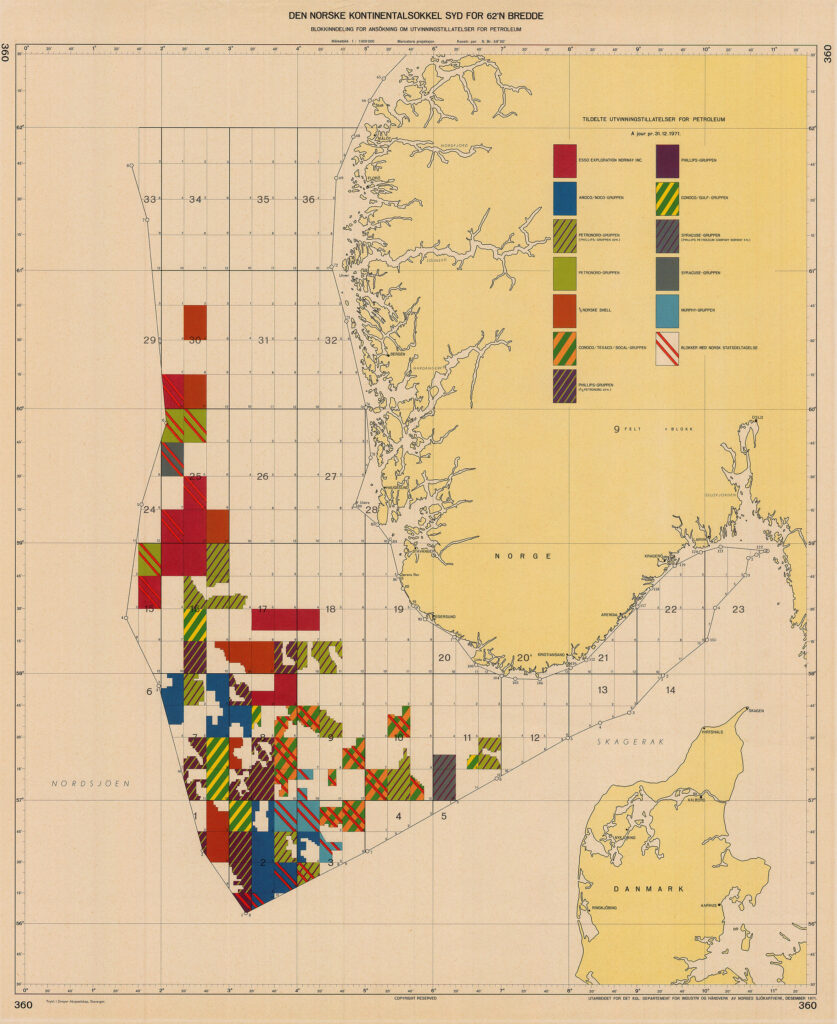

In connection with the third licensing round during the mid-1970s,[REMOVE]Fotnote: A licensing round is the term for a collective award of production licences which allow the recipient oil companies (licensees) to explore for and produce petroleum from designated areas of the NCS. the Ministry of Industry had asked Statoil to list the blocks it believed should be controlled by the state through the company. The ministry had decided as early as 1970 that a number of “key” blocks should be set aside. These particularly interesting areas of the NCS would be reserved for greater state and national participation than had been achieved until then through the licensing system.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 95 (1969-70) to the Storting, Undersøkelse etter og utvinning av undersjøiske naturforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel m.m, Ministry of Industry and Craft, Oslo. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1969-70&paid=3&wid=d&psid=DIVL896.

In practice, the foreign companies had more or less dominated the first two licensing rounds in the mid to late 1960s. They obtained operatorships and holdings, and largely determined the licence terms – even though the government later negotiated a degree of state participation.

The blocks reserved either had a big potential, were adjacent to the boundary line with other national sectors of the North Sea, or lay close to known discoveries.

Key blocks

When the third-round blocks were put on offer in June 1973, the issue of the key blocks had become more specific and the ministry decided to reduce their number.

The announcement stated that nine blocks along the boundary with the UK and close to the border area had been held back. They were 1/2, 1/9, 24/3, 24/6, 24/11, 24/12, 25/7, 34/7 and 34/10.

That same autumn, Statoil was asked to present an overall plan for the best way to utilise the reserved acreage. This was extremely important for the company, but also represented an extensive and time-consuming job. Its main analysis was completed in January 1974, when a 60-page report was submitted to the ministry.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A, 2008, Norges evige rikdom oljen, gassen og petrokronene: 135.

The company had been given full freedom of action in conducting the analysis, and held meetings during the autumn of 1973 with all the companies and groups which had expressed an interest in collaborating on utilising the key blocks. These discussions yielded substantial quantities of geological and geophysical data, and confirmed Statoil’s view that 34/7 and 34/10 were particularly interesting.

Block 34/7 was later awarded to Saga Petroleum and includes the Snorre field among other assets.

Statoil had designated 34/10 as its principal choice since the autumn of 1973. It would eventually become the company’s first development assignment, and the first field on the NCS developed by a domestic company. This acreage came to set its stamp on Statoil’s development – and technological progress – on the NCS.

In a memorandum to the board dated 8 February 1974, CEO Arve Johnsen described how he envisaged that the key blocks should be managed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Memorandum to the board, doc no 69/74, 10 October 1974, SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Abb/L0002: Styremøter Statoil, 1974. Accessed at https://www.digitalarkivet.no/db60034662000735 This called in his view for a staged exploitation of the acreage, both to accord with the Storting’s call for a moderate pace of oil production and to give Statoil time to deal with the awards and adapt.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 30 (1973-74) to the Storting, Virksomheten på den norske kontinentalsokkelen m.v, Ministry of Industry. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1969-70&paid=3&wid=d&psid=DIVL896.

The company also had to take account of the ministry’s presumption that Norsk Hydro and Saga, Norway’s two other oil companies, would be involved in one of the licences.

Other issues of principle underlying Statoil’s prioritisation were that the Norwegian state – via the company – should obtain the best possible return from the key blocks, and that the organisation of development and production should secure the largest possible share of the petroleum value.

An express political goal was for Norway to become an independent, self-sufficient oil nation. Building up national technological expertise was crucial for achieving that ambition. Where Statoil was concerned, the target was to become a technologically competent operative company. Through the Statfjord development, Statoil had gradually expanded a shadow organisation and recruited a number of specialist personnel. Agreements to be entered into with foreign companies had to include requirements that Statoil would learn from their expertise. The company was to be able to take over as operator on the key blocks within a reasonably short space of time – without “reasonably” being more closely defined. Another aspect of this managed Norwegianisation was the strengthening of industry in mainland Norway by ensuring petroleum deliveries through Statoil’s operations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter from Statoil to the Ministry of Industry and Craft, 8 February 1974, signed by Jens Christian Hauge, chair. SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Abb/L0002: Styremøter Statoil, 1974, Accessed at https://www.digitalarkivet.no/db60034662000739.

Criteria applied by the company in choosing prioritised key blocks were that a possible field must contain oil, be large, and lie in a water depth accessible to the technology of the day. Several had been assessed and considered promising: 30/6 (which turned out to contain Oseberg), 34/7 (Snorre), 34/8 and 34/10. The last of these satisfied all three of the requirements set, while 34/7 lay in deep water and depended on technical advances to be producible, and it was thought likely that 30/6 held more gas than oil.

Block 34/10 was characterised by a complex geology, with fracturing and many faults. But this was precisely what offered a unique opportunity for moving Statoil towards its goal of becoming a technologically competent and technology-driven company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B and Statoil, 2006, 34/10: Oil the Norwegian way – a story of boldness, Statoil, Stavanger: 58.

Its final prioritisation placed 34/10 at the top of the list, with 34/7 in second place.

Statoil proposed that block 1/9, which was lower down the ranking, should be exploited in collaboration with a foreign partner. A discovery there could provide substantial revenues for the company at a relatively early stage because it was close to the Ekofisk complex, and existing infrastructure was therefore available. This acreage was awarded on 27 August 1976 with Statoil as operator, and proved to contain the company’s first discovery. It was named Tommeliten Alpha.

Where the rest of the blocks were concerned, Statoil did not envisage anything being done with them for the moment.

Fourth round

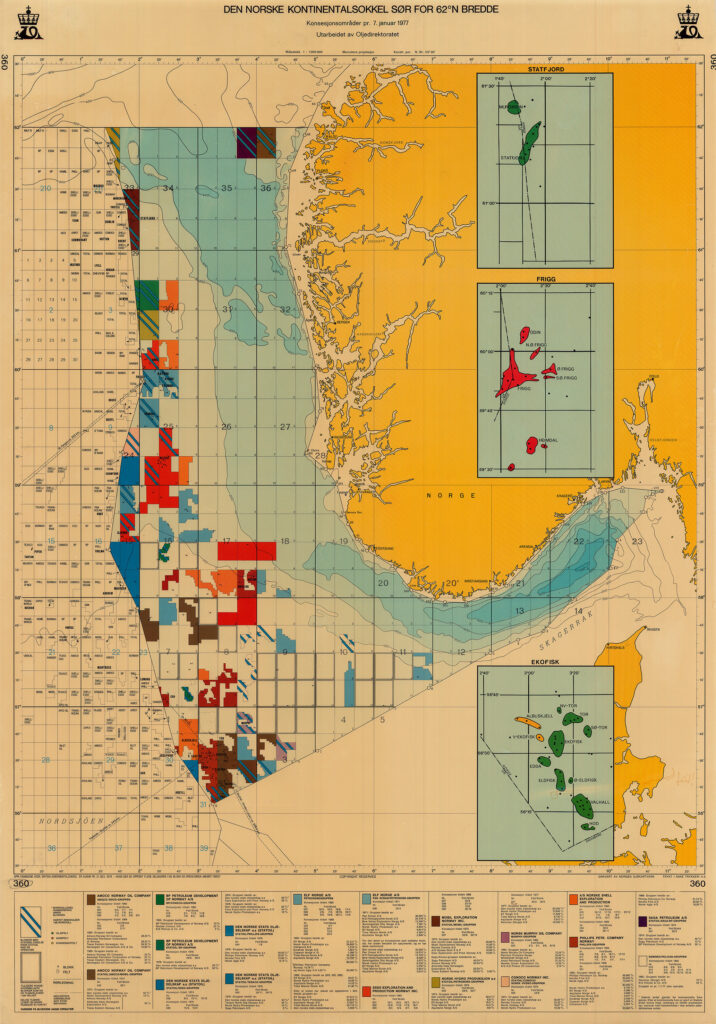

By 1977, the time had come for a new licensing round. The Norwegian economy was stagnating, with activity in the North Sea waning. Since drilling on blocks awarded in 1974 and 1975 had yielded largely negative results, making new acreage available could help to maintain exploration.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 142 (1976-77) to the Storting, Om utlysning og tildeling av blokker på kontinentalsokkelen, og om boring etter petroleum i statlig regi, Ministry of Industry, Oslo: 3. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1976-77&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL400. Activity could not be allowed to decline if Norway wanted to maintain a positive impact from the offshore industry, particularly for its hard-pressed shipbuilding sector.

As a first step, the plan was to award a limited number of blocks – probably five-six. Based on the results of drilling these, the ministry would decide whether to license more.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 142 (1976-77) to the Storting, Om utlysning og tildeling av blokker på kontinentalsokkelen, og om boring etter petroleum i statlig regi, Ministry of Industry, Oslo: 3. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1976-77&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL400. The principle established with the licensing round in 1974 that Statoil would hold a 50 per cent interest in all blocks awarded was maintained. This percentage could also be increased were a commercial discovery made.

By now dubbed the golden block, 34/10 had attracted particular attention. Statoil was not the only company keen on it – no less than 19 of the world’s leading oil companies expressed an interest. This block was considered to have such great potential that it called for special treatment, and the government decided to award it ahead of the regular round. The Labour Party was in government and worked hard, in concert with the unions, to secure Statoil as sole licensee.

In proposition no 142 (1976-77) to the Storting, the ministry recommended that 34/10 be awarded outside the regular round – as had also been done with Statfjord – and to Statoil alone.

A North Sea blowout disrupted these plans. On 22 April 1977, a month after the proposition had been approved by the Council of State, oil flowed uncontrollably from a well on the Ekofisk field’s Bravo platform and caused questions to be asked about offshore safety. Was this good enough and did the Norwegian authorities have it under proper control? And what about contingency planning for oil spills? The Bravo blowout clearly demonstrated that the government had been caught unawares and that preparedness was far from adequate.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meyer, J, 1977, Ukontrollert utblåsing på Bravo 22. april 1977 Norwegian Official Reports (NOU) 1977:47, Universitetsforlaget, Oslo. The commission of inquiry submitted its report to the Ministry of Justice on 10 October 1977. In line with the precautionary principle, the decision was taken to halt all awards and licensing until an investigation of the accident had been completed. This meant that proposition 142 was not considered by the Storting and the awards were adjourned.

The ministry nevertheless continued its work, and a new proposition was submitted in December 1977. This largely conformed with the original proposals presented in March. But one significant change was that, instead of being the sole licensee, Statoil would now have Hydro and Saga as partners.

Proposition no 72 (1977-78) to the Storting stated that “… participation in a relatively prospective block would appropriate in that Hydro and Saga can help to ensure the many tasks we face in the oil sector are performed in the manner the Storting expects”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 72 (1977-78) to the Storting, Om utlysning og tildeling av blokker på kontinentalsokkelen, og om boringer etter petroleum i statlig regi. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1977-78&paid=2&wid=a&psid=DIVL895. The ministry emphasised that the block was regarded as sufficiently promising to potentially “[…] promote the organisational and financial basis for the development of and collaboration within the Norwegian oil industry and thereby to maintain and protect a Norwegian petroleum milieu.”

Continued favouritism towards domestic players at the expense of foreign oil companies was displayed by these proposals. The Norwegianisation policy aimed primarily to create a broad national oil community which would make the country less dependent on foreign expertise and capital. While the main part was assigned to Statoil, Hydro and Saga had important supporting roles.

Over its first five years, the state company had built up an ever-stronger position. Now the two private players were to be given a leg up. The ministry proposed that they should each receive five per cent of 34/10, while Statoil got the rest. And the latter continued to be favoured, since Hydro and Saga were both also required to pay 10 per cent of the exploration costs.

This solution was intended to give all the Norwegian companies a stronger position on the NCS. No role was envisaged for foreign participants. That meant their capital and expertise was no longer seen as so important for developing the NCS. The earlier concern that the international companies might pull out did not appear to worry the politicians. In contrast to earlier political signals, the ministry now believed that the foreigners were welcome to shift their activities elsewhere if their role was reduced. That opportunity was not available to Hydro and Saga, and new assignments on the NCS would represent an important basis for their continued existence. Were they given less to do, it would be harder for them to retain the expertise they had acquired.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 72 (1977-78) to the Storting, Om utlysning og tildeling av blokker på kontinentalsokkelen, og om boringer etter petroleum i statlig regi. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1977-78&paid=2&wid=a&psid=DIVL895.

Foreign companies reacted to the recommendation with fears that this was the start to a complete nationalisation of the NCS, while Hydro was shocked that it received such a small slice.

The government came under pressure from every side – Hydro, the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) and the non-socialist parties. Hydro naturally wanted part of the best block on the NCS. The LO – and particularly members at Hydro plants – also called for the company to get rights to the golden block. For their part, the non-socialists – and the Conservatives in particular – pressed for greater participation by the two private companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kvam, Ragnar Jr, 26 January 1978, “Får Hydro 10 prosent andel i gullblokken?” They wanted to shift the centre of gravity in order to improve the balance between the three Norwegian players. Statoil’s privileged position had been politically contentious before, as it was now and would be again.

The issue was sent to the Storting’s standing committee on industry. In its consideration of the proposed award, the division between Labour and the Conservatives over their views of Statoil and its relationship with the private Norwegian companies became plainly visible. Where the Conservatives were concerned, it was a “remarkable misapprehension that [Hydro and Saga] are less national than Statoil”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Odd Vattekar, Conservative, Storting proceedings, 16 March 1979: 2269. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1977-78&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL382&pgid=b_0931. The party was dissatisfied with the size of the private-sector share and, together with the oil development sceptics from the Centre, Liberal and Social Democrats, threw a spanner in the government’s works.

The Conservatives primarily sought larger holdings for Hydro and Saga. It also wanted Norse Petroleum – one of the “people’s joint stock companies” which had raised capital by selling shares direct to ordinary Norwegians – to have a one-per-cent stake, and not a big reduction in the carrying of Statoil’s costs by the private licensees.

During the hearing by the industry committee, Hydro demanded a 15 per cent interest and Saga called for 10 per cent. They had admittedly accepted five per cent apiece in advance, but maintained that they had been forced to yield to pressure from Labour. It was time for one of the many oil-policy compromises between Labour and the three largest non-socialist parties.

The government was not only subject to external pressures, but also faced an internal conflict over the golden block. A number of Labour representatives expressed strong opposition to the final outcome.

This solution was characterised by the pragmatic approach which has typified Norwegian oil policy formation. Hydro was to get nine per cent and Saga six, leaving Statoil with 85 per cent. The junior partners also had to pay 1.5 times their share of the exploration costs. Since the probability that the golden block contained large quantities of petroleum was considered very high, an 85 per cent holding was not considered an excessive risk. While no foreign oil company was included in the allocation, Statoil was to receive considerable assistance from commissioning Esso to serve as its technical guide and assistant.

Within two years, the company had twice struck it rich – first with a 50 per cent holding in Statfjord and now by landing 85 per cent of the golden block and the operatorship.

Statoil also emerged well in every respect from the fourth licensing round itself. It secured three other operatorships – which proved to contain Huldra, Veslefrikk and Oseberg. Troll was the only fourth-round discovery with a foreign operator in the shape of Norske Shell. But that company was only allowed to handle the field development, and had to transfer the operatorship for the production phase to Statoil – which also had a stake of no less than 75 per cent.

Awards in the third and fourth rounds

Third licensing round

038 – awarded 1 April 1975, operator Statoil 50% (Varg and Rev), first well 15/12-1 – Ross Rig – oil discovery (later awarded to production licence 1034).

039 – awarded 1 April 1975, operator Conoco, Statoil 50% – dry.

040 – awarded 1 April 1975, operator Hydro, Statoil 50%. Martin Linge, proven 1978, plan for development and operation 2012.

041 – awarded 1 June 1975, operator Saga, Statoil 50%.

042 – awarded 1 June 1975, operator Amoco, Statoil 55% – dry.

043 – awarded 6 August 1976, operator BP, Statoil 50% – Martin Linge.

044 – awarded 27 August 1976, operator Statoil 50% – Tommeliten (1/9), proven 1977-78.

045 – awarded 3 December 1976, operator Statoil 50%.

046 – awarded 3 December 1976, operator Statoil 50% – Sleipner.

047 – awarded 7 January 1977, operator Hydro, Statoil 50%.

048 – awarded 8 February 1977, operator Hydro, Statoil 50% – Gina Krogh.

049 – awarded 23 December 1977, operator Agip, Statoil 50%.

Between rounds

050 – awarded 16 June 1978, operator Statoil 85% – Gullfaks.

Fourth licensing round

051 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Statoil 50%, Huldra, proven 2000.

052 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Statoil 50%, Hydro 10% – Veslefrikk.

053 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Statoil 50%, Hydro 12.5%, Saga 7.5% – Oseberg.

054 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Shell, Statoil 50%, Hydro 5% – Troll.

055 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Hydro 15%, Statoil 50% – Brage.

056 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Amoco, Statoil 50%.

057 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Saga, Statoil 50% – Snorre.

058 – awarded 6 April 1979, operator Gulf 30%, Statoil 50%.