Exploration licence in Myanmar

Myanmar – also known as Burma – was governed for many years by a military junta responsible for numerous breaches of international human rights.

A political liberalisation and democratisation process got under way in the country from 2008. Among other developments, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, who had been under house arrest for many years, was finally freed in 2010. She had been arrested for helping to found the National League for Democracy in 1988. More democratic elections were held in 2010, and economic sanctions against Myanmar were relaxed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://snl.no/Aung_San_Suu_Kyi.

Statoil had been keeping a close eye on developments in the country since 2011. It had forged good relations with the national authorities through several visits. The company had also been in continuous dialogue with the Norwegian government on the possibility of becoming established there, and had gathered information from other Norwegian companies already operating in Myanmar.[REMOVE]Fotnote: TU, 26 March 2014, “Statoil går inn i Myanmar”.

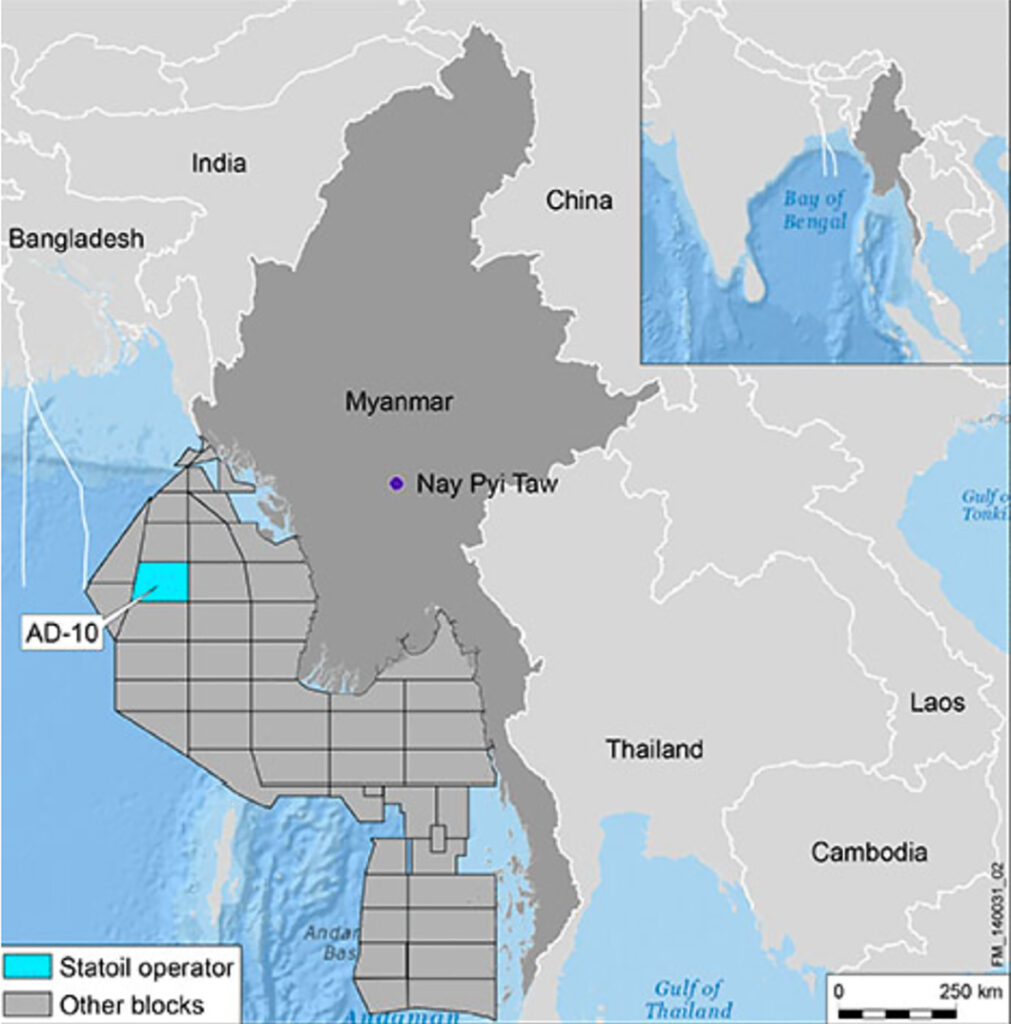

Exploring in the Bay of Bengal

Statoil applied in 2014 for licences covering two blocks, but secured only one. This was located in the Bay of Bengal, Statoil had the operatorship and shared the holding 50-50 with ConocoPhillips.

Covering more than 9 000 square kilometres, the acreage lay about 200 kilometres offshore in roughly 2 000 metres of water. The company had undertaken to conduct an impact assessment focused on environmental and social considerations, and to acquire two-dimensional seismic data during an initial exploration phase of 2.5 years. The partnership would then decide whether it wanted to continue to a three-year exploration phase.

Like many of the areas where Statoil was involved, the area to be investigated was large but little explored. It offered a potential long-term opportunity, but with considerable uncertainty related to the geology. In a press release on the licence award, Erling Vågnes, senior vice president for exploration in the eastern hemisphere, observed that working in such frontier areas was in line with Statoil’s exploration strategy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/no/news/archive/2014/03/26/26MarMyanmar.html. The company was concerned to make more discoveries internationally in order to expand its resource base.

At the time, Statoil became involved in Colombia (2014), Nicaragua (2015), South Africa (2015), Turkey (2016), Uruguay (2016) and Argentina (2017) as well as Myanmar.

Finished in Myanmar

Statoil pulled out of Myanmar almost as quickly as it had piled in. It left in 2017, after deserting Kazakhstan and Mozambique in 2014. The company announced that this had nothing to do with the political position in Myanmar, which had deteriorated again after a few years of improvement.

Aung San Suu Kyi had become head of government after a democratic election, but the position of her administration was fragile. Its remit was confined to civil matters, with the military retaining full control in its self-defined sphere of security policy. That include the “Rohingya problem” – a Muslim ethnic minority which was attacked by the military in Rakhine state. The result was a flow of Rohingya refugees to neighbouring countries. Aung San Suu Kyi came in for international criticism for her failure to denounce the military’s brutal behaviour.

While these developments were under way, Statoil withdrew from the country – but for geological reasons. The company had to decide whether it wanted to move to exploration drilling by March 2017, and the answer was negative. Based on the data acquired about and from licence A-10, the opportunities for making a commercial discovery there were regarded as too small. A high level of tax also contributed to the decision.

This was in line with Statoil’s strategy. The company would enter new areas early, but be prepared to throw in its hand quickly.

The refugee problem in Rakhine state, close to the exploration site, did not help to trigger Statoil’s withdrawal decision. But the company’s spokesperson said it had followed developments closely and had neither people nor activity there.[REMOVE]Fotnote: DN, 3 December 2017, “Midt under flyktningkrisen forlater Statoil Myanmar. Men det skyldes først og fremst geologien”.

Things could have taken a more complicated turn if Statoil had remained. A possible gas discovery combined with the resumption of power by the military would have presented management with a substantial ethical dilemma.

arrow_backSouth Korea – a key fabricatorStep towards savingsarrow_forward