Expertise was the key

Where was the workforce to come from? Would it be possible to find people with the right qualifications in a country where oil had only been discovered two and a half years earlier? Answers to these questions were sought both at home and abroad.

First appointments

The Storting decision to establish Statoil left the board responsible for determining the company’s organisational model. It decided that the initial build-up would benefit from adopting a flat structure and “avoiding a commitment to a fixed pyramidal organisation”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s, 5 December 1972. Accessed at https://www.digitalarkivet.no/oe10511205101014.

Relevant candidates for senior posts should have the necessary variety of expertise to form a management team, with responsibilities assigned by the CEO. This group’s job would be to resolve issues confronting the company, and to function as a project team for Statoil’s expansion and organisation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s, 5 December 1972. Accessed at https://www.digitalarkivet.no/oe10511205101014.

At the beginning of 1973, Statoil had two employees. That figure had risen to 54 by the end of the year and reach 118 during 1974. The average age of this workforce was 32 years and 10 months. A group of young, professionally qualified and motivated employees had been assembled to help construct the new company.

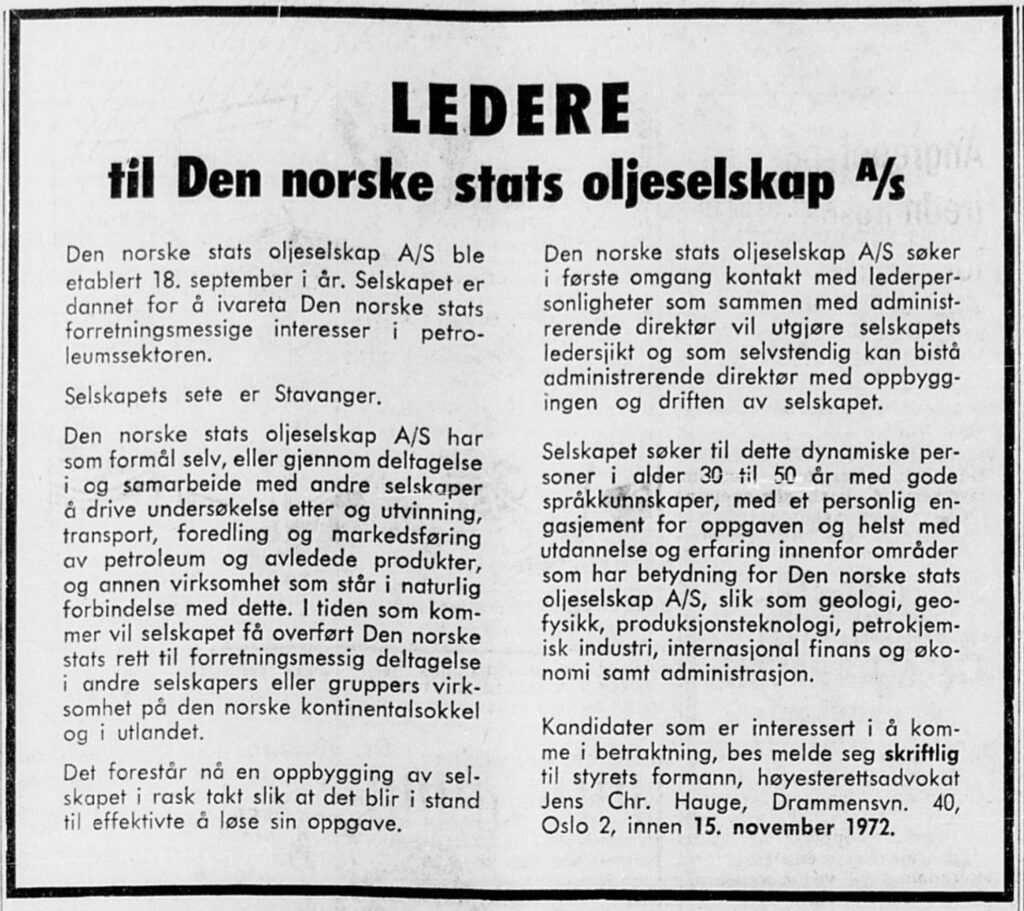

CEO Arve Johnsen informed the board at its meeting of 5 December 1972 that 475 applications had been received for senior posts. He held the first conversations with relevant candidates three days later, with secretary Marit H Falck as his first appointment.

Olav K. Christiansen was the first recruit to the management team. With a US education and experience from Standard Oil of California as well as the Ministry of Industry in Oslo, he became head of the technology department.

The same title was given to the next appointee, Helge Skinnemoen, who had an MSc in engineering from Germany’s Technical University of Darmstadt and experience in the USA with the Norwegian industrial group Norsk Hydro. He was to lead the company’s commitment to refining and petrochemicals.

Jon Ruud, who held a law degree from the University of Oslo, became responsible for legal affairs and contracts. He had served with the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Geneva before joining Hydro in 1966. From day one, Ruud worked on negotiations and the job of building Statoil’s legal department.

Erik Schanche, appointed to lead the department for marketing and budget planning, had studied at the universities of Uppsala and Missouri and had experience from the Norwegian foreign service and shipping.

Responsibility for administration went to Christian Halvorsen, who had studied at the Norwegian School of Economics and in California, and had worked both as an industry consultant and a finance manager.

Tor Espedal became head of the company’s finance department in September 1973, while the final team member appointed was Arne H Halvorsen to take charge of information and government affairs.

All these appointees had relevant experience from the oil sector or foreign companies with the exception of Halvorsen, who had acquired unusually detailed knowledge of the petroleum industry as a journalist at local daily Stavanger Aftenblad.

Johnsen faced a bigger challenge when he came to recruit geologists, geophysicists and petroleum engineers. Although Norway had plenty of geologists and engineers, few had experience from the oil and gas industry. The CEO had to turn to the USA to find key personnel in these disciplines.

The board gave him the authority to recruit “two to four foreign experts at the management/middle management level” in exploration and petroleum technology.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s, 1 June 1973, SAST/A-101656/0001/A/Ab/Aba/L0001, accessed from https://www.digitalarkivet.no/oe10511205101027. Johnsen flew with Christiansen and Arne Lervik, Statoil’s first geologist, to the USA in the early summer of 1973 to interview relevant candidates.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A, 1988, Utfordringen: Statoil-år, Gyldendal, Oslo: 62.

That resulted in the recruitment of Americans Eugene B Muehlberger from Shell and Phillip H Halstead from Chevron as managers for drilling and production and for exploration respectively.

Two more Americans joined the company in the autumn of 1974. George A Bell got the job of building up the geophysics section, while Donald I Milton became responsible for petroleum geology.

Statoil had finally put specialists in place to lead the build-up in expertise on exploration, drilling and production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, 1992, Fra vantro til overmot?, Norsk Oljehistorie, vol 1, Leseselskapet, Oslo: 368. Six departments had been established: exploration, technology, marketing, finance, law and contracts, and administration.

The board followed a conscious strategy of avoiding the term “vice president” in favour of titles which indicated the area of responsibility covered and at what level.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s, 21 June 1973, SAST/A-101656/0001/A/Ab/Aba/L0001, accessed from https://www.digitalarkivet.no/oe10511205101030

An early organisation chart. Source: Regional State Archives in Stavanger, PA 1339 – Statoil ASA, Series Aa – meeting books, minutes, negotiating minutes, etc, archive section 7.

Enhancing expertise with state support

Statoil wanted to be awarded operator responsibility for exploration and production licences, and had to build an organisation of experienced personnel as quickly as possible.

Its early years accordingly involved an intense learning process. That was pursued partly through formal education, study trips abroad and training at other companies in Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board meetings in Statoil. Archive reference. SAST/A-101656/0001/A/Ab/Abb/L0003 Arkiv Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA Section/folder L0003, https://www.digitalarkivet.no/db60034663000799.

With each block licensed for exploration and production by the state, the international oil companies receiving shares were required to help train employees from their Norwegian partners. The same applied to Statoil, which used its position to secure assistance with training.

During its early years, a number of employees were seconded to such oil companies as Elf Aquitaine, Mobil, Conoco and Shell. Experts at these firms, in addition to their normal duties, were to help ensure that well-educated Norwegians secured specialist knowledge in strategic oil disciplines as quickly as possible.

Another method much used for technology transfer to Norway was to dispatch Norwegians abroad for study periods and courses of varying duration at other companies. Many of Statoil’s early employees were seconded in this way.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moland, Elisabeth Ugland, 2011, Fra lærling til mester: Kunnskap og kompetansebygging i Statoil årene 1972-1986, MSc thesis, University of Agder, Kristiansand, accessed from: https://uia.brage.unit.no/uia-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/139504/HI-500%202011%20Vsr%20Masteroppgave%20Elisabeth%20Ugland%20Moland.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

In addition to expertise enhancement through secondment, further education and study trips, two collaboration agreements meant a great deal for reaching the goal of becoming a technologically competent company. These involved exploration training at Esso and the collaboration agreement with Mobil over the development of the Statfjord field.

arrow_backClarifying Statoil’s governanceThe first oil crisisarrow_forward