Norsk Hydro – government instrument in oil policy?

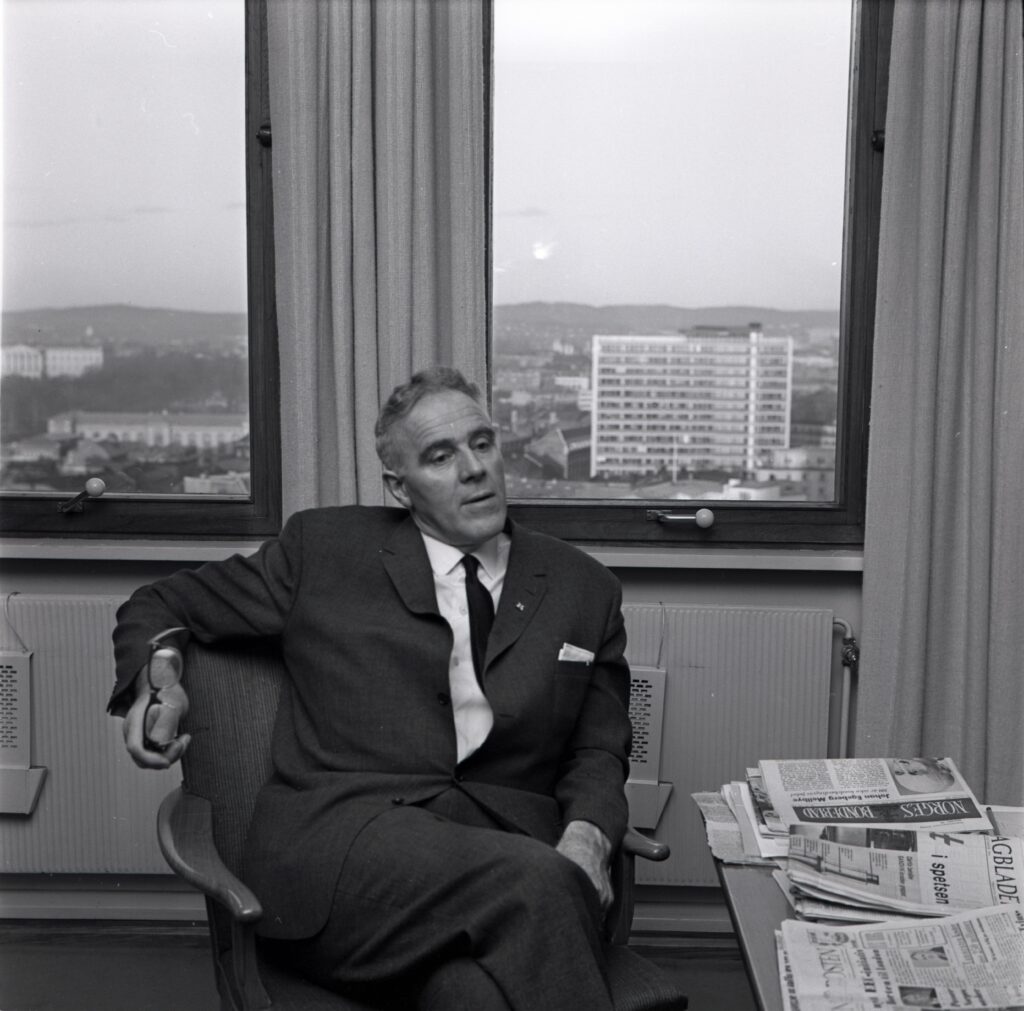

The idea that the government should secure a majority shareholding in Hydro, which was primarily involved in chemicals and metals and was a big oil consumer, originated with CEO Torvild Aakvaag. In a November 1970 memorandum, he formulated the group’s ambitions very clearly – it was to become the government’s instrument in developing the Norwegian oil industry.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johannesen, Finn Erhard, Rønning, Asle and Sandvik, Pål Thonstad, Nasjonal kontroll og industriell fornyelse, Hydro 1945–1977, (2005): 319.

A national instrument

Hydro was the Norwegian company most heavily involved from the start in North Sea petroleum operations. As a participant since 1965 in the Petronord group together with seven French companies, it had interests in exploration and development licences covering 12 offshore blocks.

To spread their risk, the Petronord partners had entered into a swap agreement in 1967 with the Phillips group. Each side obtained a 20 per cent share of the other’s licences. This deal proved gilt-edged for Hydro after the Ekofisk discovery. It had secured a 6.7 per cent interest in this field, which represented very good start-up capital as an oil company.

Proposals to use Hydro as a political instrument faced the drawback that it had a majority of private – and to some extent French – shareholders. The Norwegian state already held 47.72 per cent of the shares, with private domestic interests owning 25 per cent, French investors holding 23 per cent and four per cent registered in other countries – including Switzerland. That brought the total private shareholding to just over 52 per cent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 323.

If Hydro was to become a national tool on the Norwegian continental shelf, the state holding would need to be increased. On 9 October 1970, Borten and industry minister Sverre Walter Rostoft wrote to Hambros Bank in London as follows:

With reference to the conversation with managing director Otto Norland at my office on 9 October this year, I hereby confirm that I am interested in increasing the Norwegian state’s proportion of the shares in Norsk Hydro A/S from 47.72 to at least 51 per cent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 63 to the Storting on the purchase of shares in Norsk Hydro A/S: 3.

The acquisition had to occur quickly and in secret to prevent rumours spreading and causing the price to go through the roof. Borten therefore dispatched Norland on a tour of Europe by chartered plane, visiting a number of centres in France, Austria, Switzerland and West Germany. The banker bought Hydro shares on his own account and subsequently transferred them to the Norwegian state. His mission was a success, and Hydro was thereby available to become the government’s oil-policy agent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johannesen et al (2005): 323.

Change of government and approach

The share acquisition became known when the Storting considered it in January 1971. But how far Hydro would become the national instrument in the petroleum sector nevertheless remained politically uncertain. Creation of a wholly state-owned oil company still had its adherents, including on the non-socialist side. In reality, the Borten government also had only a short time left, with the four coalition parties deeply divided over Norway’s relationship with Europe. Its handling of the issue of European Community membership led to a vote of no confidence in the Storting. Internal dissension within the government was so great that it could not continue.

On 17 March 1971, the Ap’s Trygve Bratteli took over as prime minister.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, Nerheim, G., & Norsk petroleumsforening. (1992). Fra vantro til overmot? (Vol. 1, p. 523). Leseselskapet.: 165-169. This change prepared the ground for a different model matured by the new governing party. A new oil company was to be built up, and would be wholly owned by the state.

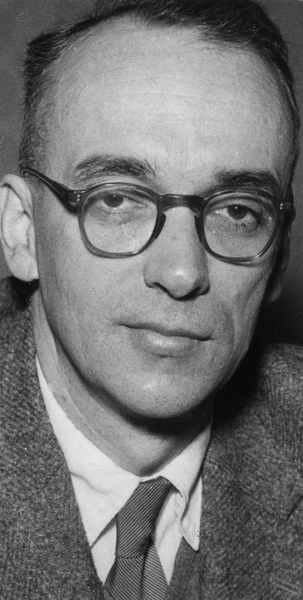

Although the Ap government lacked a majority in the Storting, the state oil company model was promoted over the following year by industry minister Finn Lied. He was perhaps the party’s most influential industrial policy-maker in the years following 1945, head of the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment for many years and a respected scientist. Lied picked Arve Johnsen, who had earlier authored a draft Norwegian oil policy, as his state secretary (junior minister). Together, they proved highly influential.

Lied commented later in an interview:

We wanted the state to be intimately involved operationally in the sector. That would allow us to learn from the ground up. We wanted a wholly state-owned arrangement. This was the nation’s wealth. We didn’t have that form of control over Hydro, which was a limited company subject to the ordinary legislation governing such enterprises. That did not make it appropriate as the government’s instrument. The only possibility for securing an instrument was to have full ownership.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Finn Lied, interviewed by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) in its My Life series.

The report from the Knudsen commission, which had assessed how state involvement should be organised inside and outside the Ministry of Industry, was presented on 24 March 1971 and marked an important preliminary to the decision on establishing a state oil company. This was a week after the government which commissioned the inquiry had resigned. The question then was whether its recommendations remained politically feasible after the change in administration.

arrow_backOil policy after the Ekofisk discoveryPossible and impossible oil company modelsarrow_forward